-

1/6

1/6

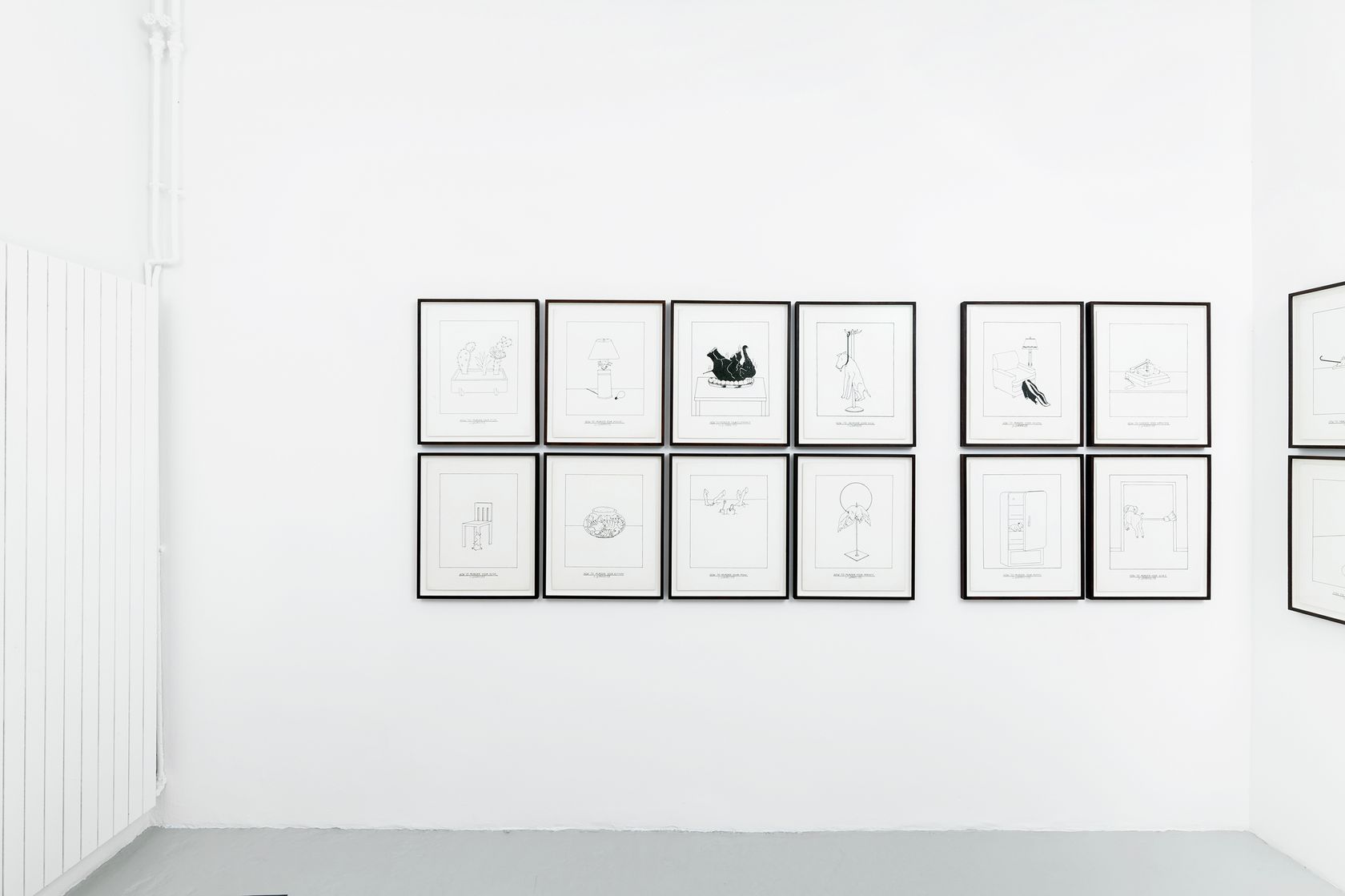

Steve Gianakos, How to Murder Your Pet

-

2/6

2/6

Steve Gianakos, How to Murder Your Pet

-

3/6

3/6

Steve Gianakos, How to Murder Your Pet

-

4/6

4/6

Steve Gianakos, How to Murder Your Pet

-

5/6

5/6

Steve Gianakos, How to Murder Your Pet

-

6/6

6/6

Steve Gianakos, How to Murder Your Pet

Portrait of The Artist as a Cockroach

Among the earliest epitaphs carved into the gravestones in France’s oldest pet cemetery, in Asnières in the Paris suburbs, we can find inscriptions that repeat well-known declarations such as: “The more I learn about people, the more I love my dog,” or “Disappointed by the world, never by my dog.” Darwin believed that the intense love humans feel for their pets was reciprocal, imagining that monkeys smile at us because they are happy; unfortunately, today’s research shows that this superficial smile simply testifies to the individual’s submission to a creature better placed in the pecking order. Although it is currently impossible to scientifically evaluate love and attachment, studies in 2015 measured blood-serum levels of oxytocin, the hormone related to affection and trust secreted by humans and their faithful companions: in a dog cuddled by its human, oxytocin levels can increase by more than 50 %. With cats, this increase is limited to around 12 %.

The bond of love between humans and animals is not built on very solid foundations: according to Professor Jean-Claude Nouët, Honorary President of the French League for Animal Rights, 50 % of rapists committed acts of cruelty against animals in their childhood and 15 % of them also raped animals. For Saint Thomas Aquinas, Locke, Kant and Schopenhauer, there is a general link between cruelty to animals and violent acts committed against humans; moreover, recent sociological studies indicate that the majority of serial killers as well as simple murderers, “learned their trade” by killing or torturing animals when they were young.

For Sigmund Freud, the motive for this is sexual, so it’s hardly surprising that Steve Gianakos was attracted by the subject. In his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905), Freud postulates that the urge to commit acts of cruelty and the sexual urge are linked in early childhood by anastomosis, an interconnection that is biological. This association of sexuality and cruelty—exercised from an early age and against animals of all shapes and sizes—is quickly curbed and ideally even controlled by the emergence of feelings of pity; the ability to empathize with the pain felt by others, including animals, which inhibits the universal desire to dominate and that appears relatively late in a child’s development.

Artistically, empathy takes on an unconventional form in Gianakos’ work. In a now legendary interview with Susan Morgan in 1979, published in the second issue of the magazine Real Life1, whose cover featured a drawing from the How to Murder Your Pet series, the artist states: “My work is not nearly as offensive as the people who look at it. Just walking the streets, you see things which are much more disgusting than anything I could ever conceive of doing—people vomiting all over the place. I try to sweeten things up, I don’t try to vulgarize them. I try to take things I know exist and make them prettier, rather than trying to make pretty things more ugly. When you talk about rich ladies fucking their dogs, that’s an example of something it would be impossible to vulgarize because it’s already too vulgar. So, the only way to prettify it is to make a nice picture of a rich lady fucking her dog. At least that would appeal to some people.” In 1945, in Bruno Munari’s book for children Animals For Sale, an animal salesman desperate to find the ideal companion for an invisible child, finally discovers that rather than an armadillo, a pink flamingo or a porcupine, what the child really wants is a roast chicken with fries!

In the above-mentioned interview, Gianakos gives free reign to his caustic and iconoclastic humor when addressing the question of subjects of art. For example, he mockingly asks: “How many artists have already painted flowers and are going to paint flowers for the next hundred years? What’s with them and flowers? Why don’t they paint germs? How many artists have painted paramecium? Only Arp. Didn’t Arp paint paramecium? I think that was very perceptive of him.” Pushing his theory still further, he states: “I’m very fond of snots, but I’ve never sold a snot painting. I don’t think even Picasso could sell a snot picture, I really don’t.”

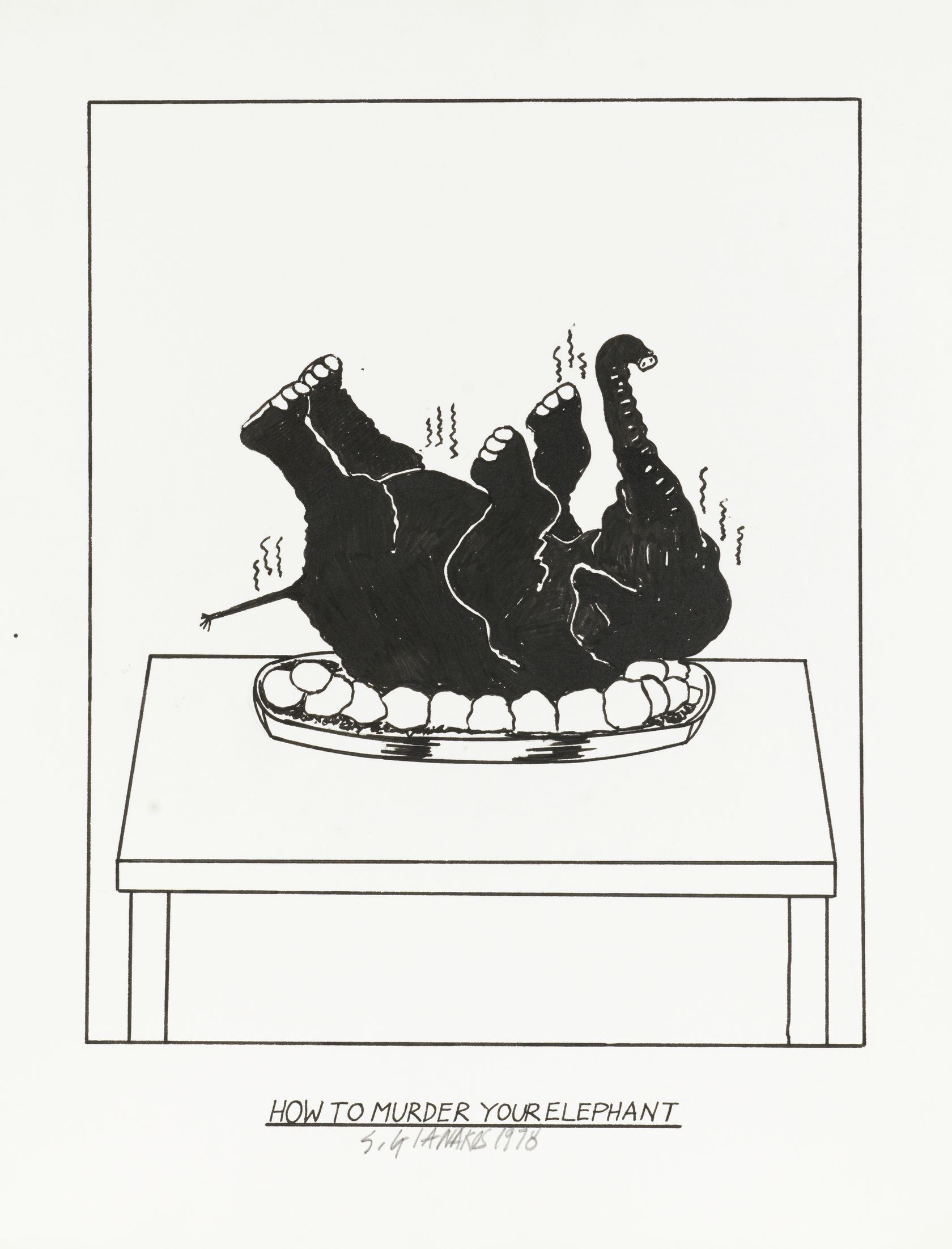

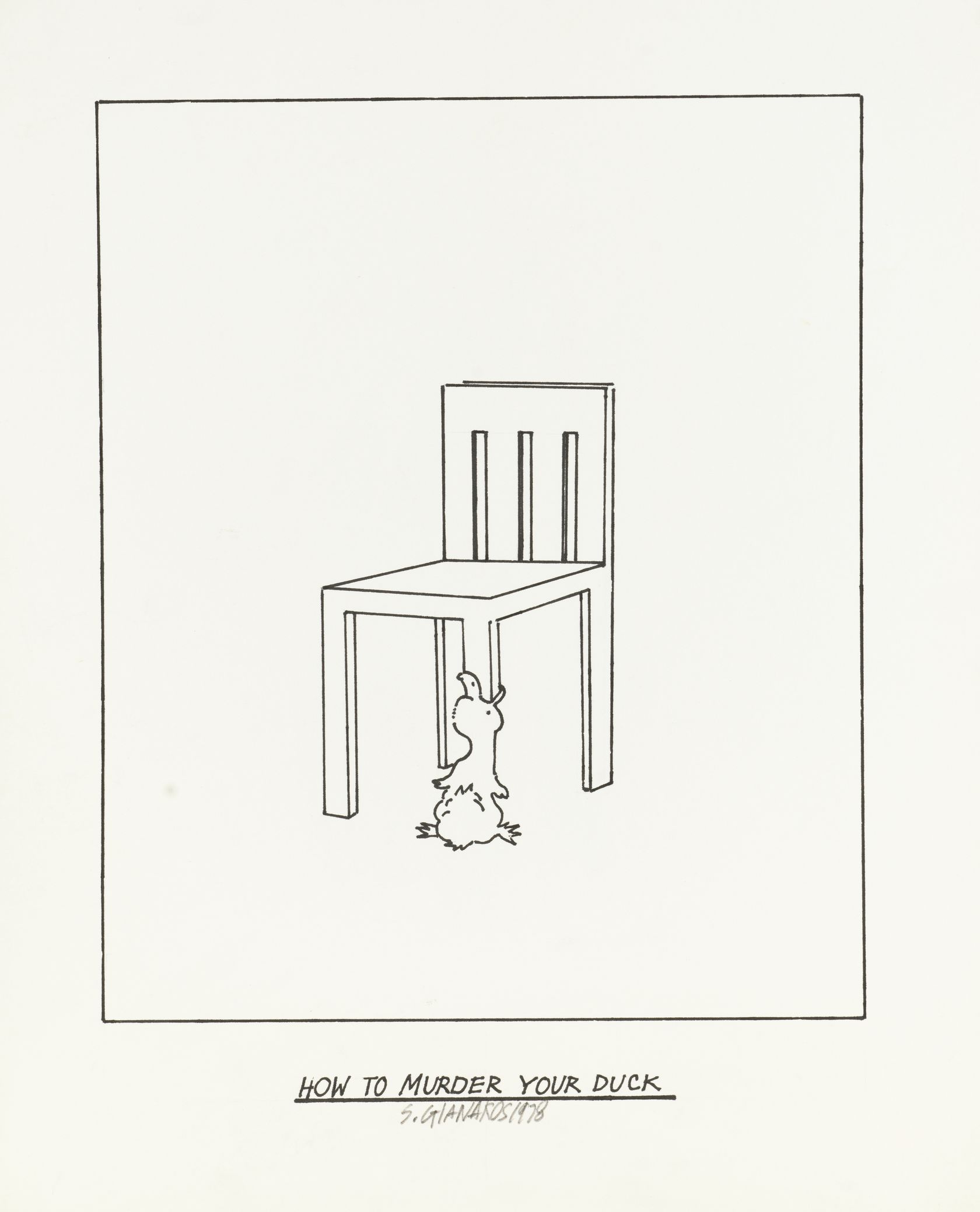

Produced in 1978, the 24 drawings that make up the series How to Murder Your Pet are perfect examples of Gianakos’ art. Firstly, as we have already seen, the subject matter is deeply linked to the primal emergence of sexuality. Secondly, the serial treatment of the subject is typical of his working practice. As he explains to Susan Morgan: “Obviously the best way to murder something is to tie a rock around its neck and throw it off a bridge, but since I’m so arty and these are all very visual, I make my idea a pretty picture.” In this series, Gianakos does not depict dead domestic animals, but rather ways of killing them, a variety of forms of torture that are all variations on the childish cruelty described by Freud. While some of them have obvious sexual connotations (the goat, stuck in a doorway with a sweeping-brush in its rectum, which at the time outraged a number of commentators), others depict the brutal—and certainly painful—encounter between an orifice and a foreign body: the guide dog with a walking stick protruding from its eye socket, the bowling ball forcing open the hippo’s mouth, the cow sucking on the exhaust pipe of a beetle (the car), the leg of a modernist chair being force-fed to a duck… There’s also symmetry in the corkscrew tail of a pig penetrating an electrical wall socket, leading to its electrocution.

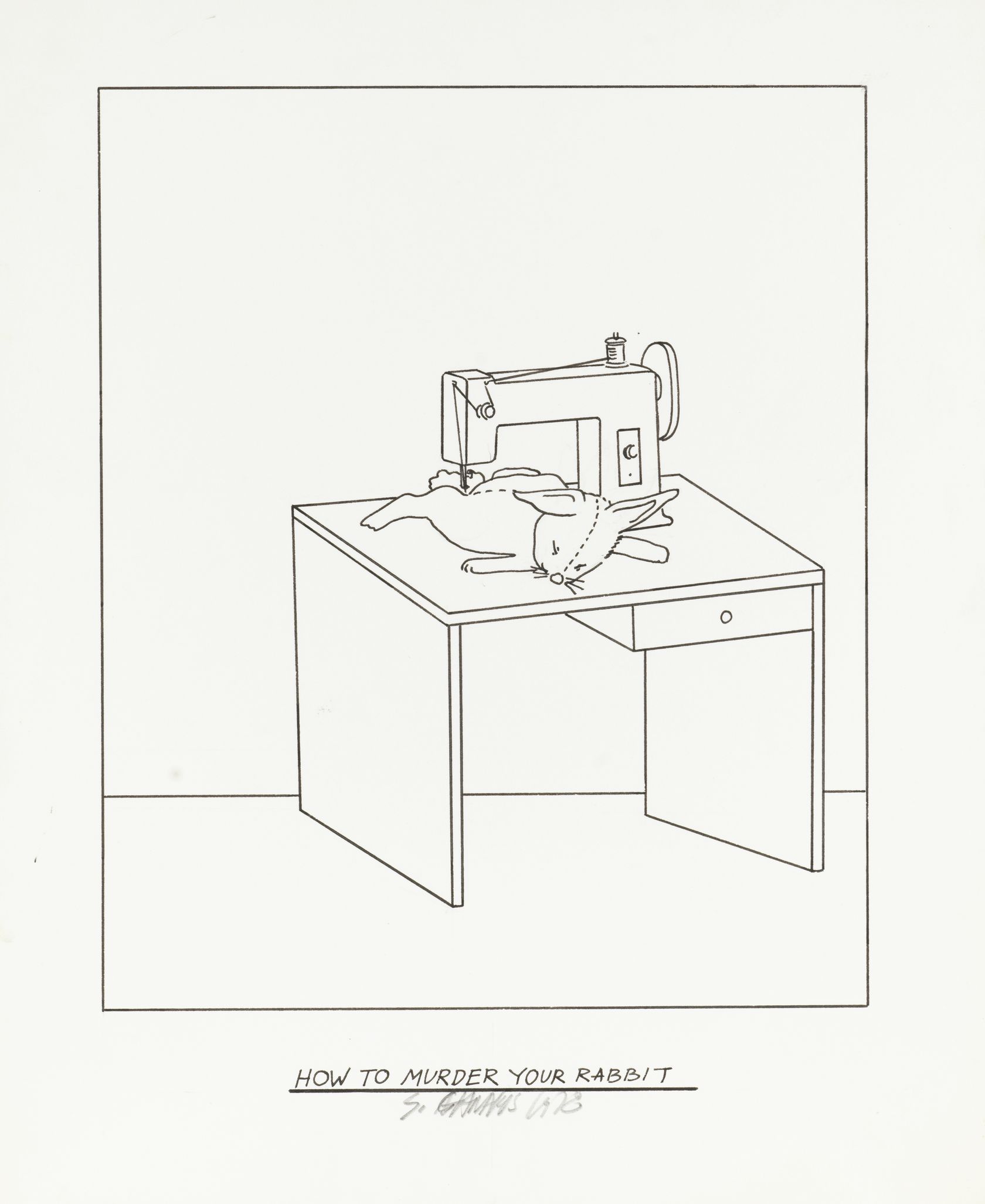

Following a logic as unyielding as the rigor of his drawing—mechanical, objective, impersonal lines that maintain the same width along the entire length of the stroke—the abuses that the artist comes up with are not simply a product of his fertile imagination but more one of a Magritte-like dialectic. One might wonder whether certain animals are simply victims of their accoutrements (the seeing-eye dog and his owner’s cane, the circus monkey and his tricycle, another dog hanged with its own leash…), while others seem to suffer due to their particular morphologies (the pink flamingo getting its feet caught in a toaster…). Gianakos favours hyperbole to make the spectator die of laughter (which is hyperbole in itself): the hamster, although used to spinning endlessly on its wheel, can’t stand the speed of a record player; the rabbit in its desire to look like a cuddly toy perishes under the needle of a sewing machine; the pony dies buried in a sandbox; the snake, perhaps in order to slither better, is flattened by an overheated iron; a turtle, although amphibious, drowns at the bottom of a cocktail glass, trapped under a straw…

While some situations may seem like a nod towards the history of art (the wheels of the monkey’s tricycle on the steps of a staircase it has come down a little too quickly, make one think of Duchamp), others emphasize the metonymic link between the pet and its corresponding environment, instilling the idea that a pet is an object like any other: the deer’s tongue hangs like a towel over the side of the Turkish steam bath, the pig’s snout looks like a female plug-socket, the skunk’s spikey claws resemble the ends of the on/off cords of the reading lamp…

The critic Peter Schjeldahl observed that for artists like Gianakos or John Wesley—before Mike Kelly or Raymond Pettibon—aware that the comic strip, elevated to a paradigm of the entertainment industry, as well as the favoured medium for the communication of anything even remotely emotional “has become to modern feeling what abstraction is to modern thought, the preferred model of subjective reality, perhaps because it is the least threatening for people too numbed by modern life to cope with anything grittier.”2

Cornered in an impasse, where the creative individual could no longer pose a threat to the society of the spectacle, these artists spontaneously responded to Guy Debord’s exhortation to go beyond art, which had at the end of the 1950s paved the way for appropriated comics (where the texts in pre-existing vignettes were replaced by theoretical extracts or propaganda) and directly realized comics (new strips made up of appropriated or original elements). The pet is me, Steve Gianakos might also have claimed, following on from Flaubert, and having included in his series of drawings animals that are not usually domesticated such as skunks, deer and elephants: “Obviously,” he declared to Susan Morgan, “any animal can be a pet, depending on where you’re living.” Any animal? That would also include artists then?

Although, as with his drawings, Gianakos can be counted on to never entirely reveal himself, or at the very least to sell his thoughts dearly, in this interview that took place during the precise period when he was doing these drawings, he let slip a profound doubt as to his position as an artist (going so far as to announce that he intended to put a stop to his artistic career and embrace that of an actor, or at least of an extra, in California), which he then resolved with a temporal pirouette: “The best artists are always dead artists, because you don’t remember anyone who isn’t good and dead. Some of the living ones are good, but I like girls better.”

Beyond simple parody, this series explores a profoundly metaphorical, bleak and even gloomy dimension in a direct echo of Barbara Rose’s famous article How to Murder an Avant-garde3, which appeared in Artforum in 1965, the same year the magazine also moved to California. Referring to two simultaneous exhibitions held in New York, one at the Metropolitan Museum concerning three hundred years of art in America, the other at the Whitney Museum, bringing together thirty artists under the age of thirty-five, the critic asks “whether or not the avant-garde has a future in America,” and supposes she “would be forced to join those already mourning its extinction, before concluding that we may yet see another victory for everything that is provincial and mediocre in American taste.”

As an epigraph to her analysis, Rose uses an extract from John Sloan’s classic textbook, The Gist of Art (1939), in which artists are also described as pets, but of a quite particular kind: “Artists in a frontier society like ours, are like cockroaches in kitchens—not wanted, not encouraged, but nevertheless they remain.”

Stéphane Corréard

_

1. Real Life Magazine, N°2, October 1979, New York.

2. Peter Schjeldahl, The Seven Days Art Columns, 1988-1990, Great Barrington Publishing, 1990.

3. “How to Murder an Avant-garde,” Artforum, vol. 4, n°3, November 1965.