-

1/10

1/10

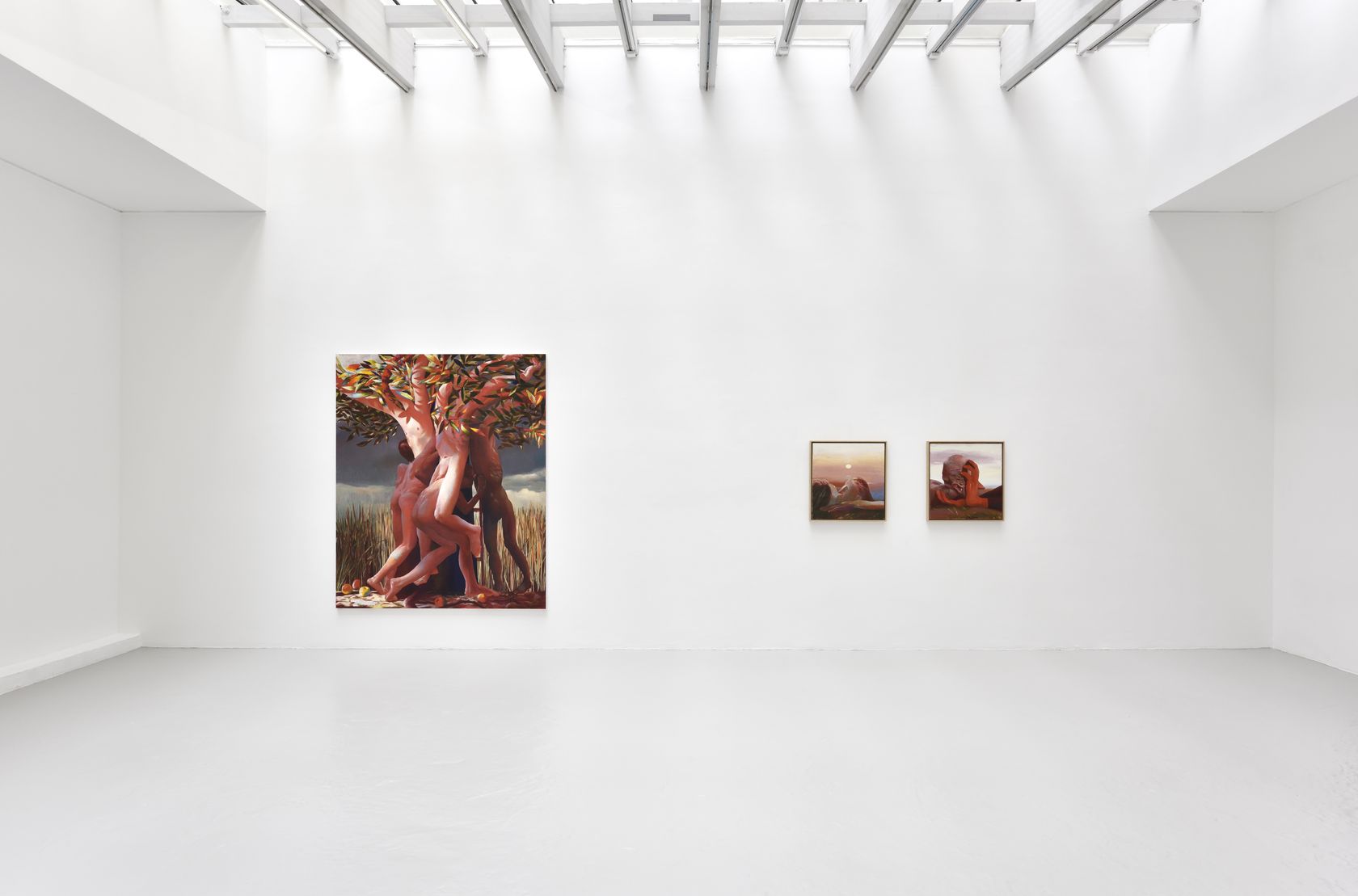

Laurent Proux, Sunburn

-

2/10

2/10

Laurent Proux, Sunburn

-

3/10

3/10

Laurent Proux, Sunburn

-

4/10

4/10

Laurent Proux, Sunburn

-

5/10

5/10

Laurent Proux, Sunburn

-

6/10

6/10

Laurent Proux, Sunburn

-

7/10

7/10

Laurent Proux, Sunburn

-

8/10

8/10

Laurent Proux, Sunburn

-

9/10

9/10

Laurent Proux, Sunburn

-

10/10

10/10

Laurent Proux, Sunburn

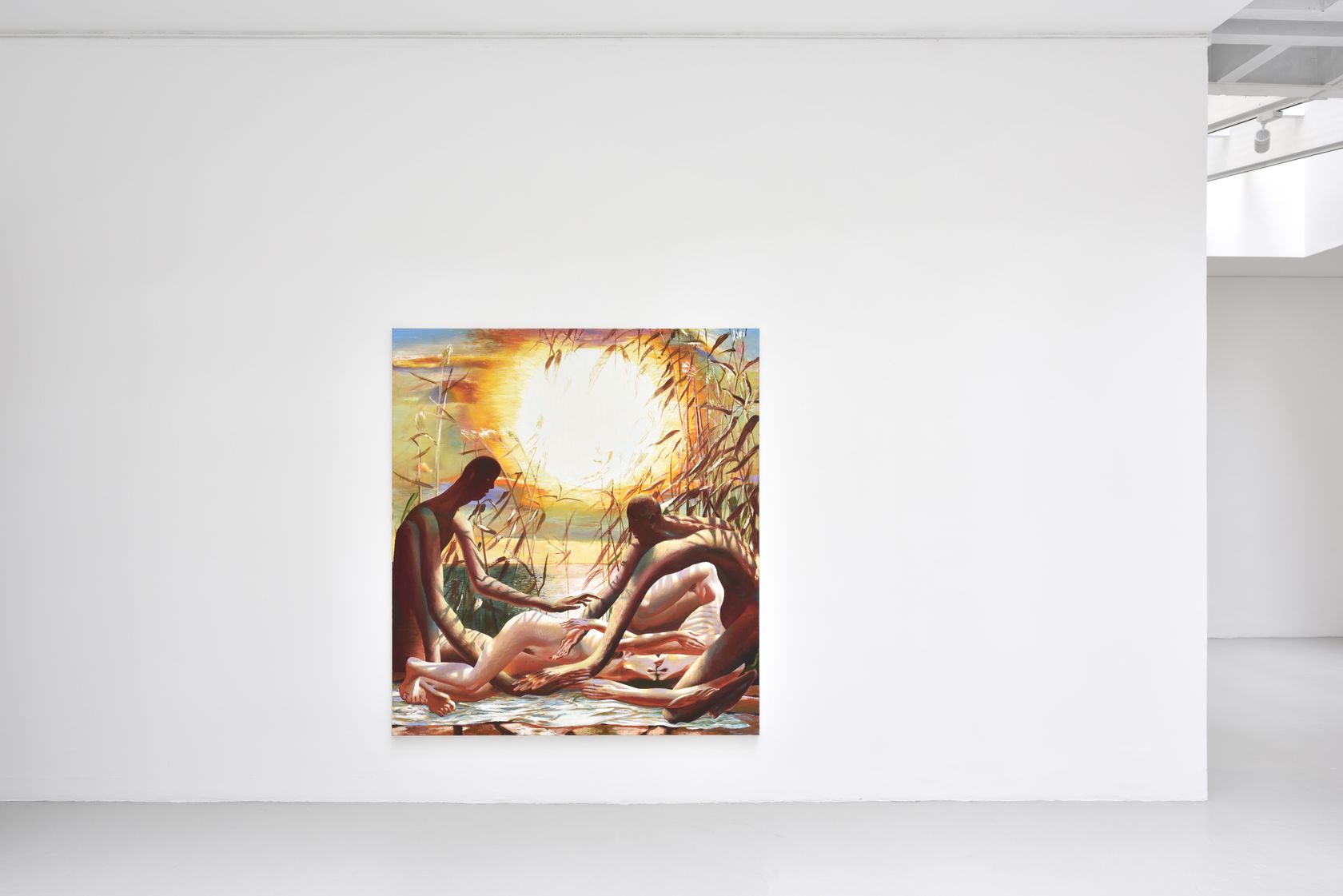

Laurent Proux’s recent paintings, created at the Casa de Velázquez, are flooded with sunlight. Madrid’s climate is obviously no stranger to the sunburned element that has given a new twist to his art. Proux’s large-format, sun-drenched paintings play on naturally contradictory levels of intensity. Light cascades through them, bathing everything in its aura, or on the contrary, carving out and incising shadows and figures. Through this approach, the exhibition Sunburn highlights two seemingly opposite scenarios: on the one hand naked characters frolic in natural surroundings, while on the other, figures labor in weaving or sewing workshops. Two universes sit side by side, the first a product of fantasy, the other one of realism. Light plays an essential, dramatic role: Proux has come up with contrasting storylines, alternating between naturalism and the supernatural. Bodies seem to be ensnared in the rays and nets of an invisible physical force. The paintings are pervaded by a certain tension, of which light is both the vector and the revealer.

The exhibition Sunburn transports us into an overheated world that is at once familiar and discordant. Large, flamboyant scenes in spectacular formats address simple subjects: eroticism and work. These two themes delve into the very heart of our individual and social existences. Everyone can relate to them. “No one can imagine a world where burning passion would definitively cease to trouble us. No one, on the other hand, can envisage the possibility of a life that would no longer be bound by calculation.”(1) “Burning passion” on the one hand, productive reason and its calculation on the other. It is clear that Proux’s paintings burn or are illuminated by what is in most cases crepuscular light. The two series reflect this naturalistic repartition, each having its own luminescence. The stylized bacchanalian romps are set in an imaginary décor, while the workshops betray a more tangible, photographic source, originating from documentary photographs of certain social settings, taken by the artist since the beginnings of his practice. Sunburn offers the spectator a vision of fiery yet tangible painting: the characters are completely absorbed in their activities, naked in the throes of sexual abandon for some, concentrated on their workplace machines for others.

The sun acts as the director of photography for the exhibition: its works, that one might describe as photosensitive, radiating a paradoxical energy, exuding a certain strangeness within clear, straightforward compositions. Its astral luminosity disrupts any initial evidence of a particular scene. Its mobile and intrusive eye penetrates the heart of each situation, insinuating itself between bodies, twisting and capturing them from any number of points of view at the same time, from above, frontally and from behind, as is the case with the bucolic frolicking. Proux approaches lighting like a baroque or classical painter, or perhaps more like a theatrical or movie director, constructing a precise scenic space with its own action, atmosphere and characters. One activity can conceal many others.

[…]

Anne Bonnin

_

1. Georges Bataille, The Tears of Eros (1961), translated by Peter Connor, 1988