-

1/11

1/11

Amy Bravo, Well Done Assassin

-

2/11

2/11

Amy Bravo, Well Done Assassin

-

3/11

3/11

Amy Bravo, Well Done Assassin

-

4/11

4/11

Amy Bravo, Well Done Assassin

-

5/11

5/11

Amy Bravo, Well Done Assassin

-

6/11

6/11

Amy Bravo, Well Done Assassin

-

7/11

7/11

Amy Bravo, Well Done Assassin

-

8/11

8/11

Amy Bravo, Well Done Assassin

-

9/11

9/11

Amy Bravo, Well Done Assassin

-

10/11

10/11

Amy Bravo, Well Done Assassin

-

11/11

11/11

Amy Bravo, Well Done Assassin

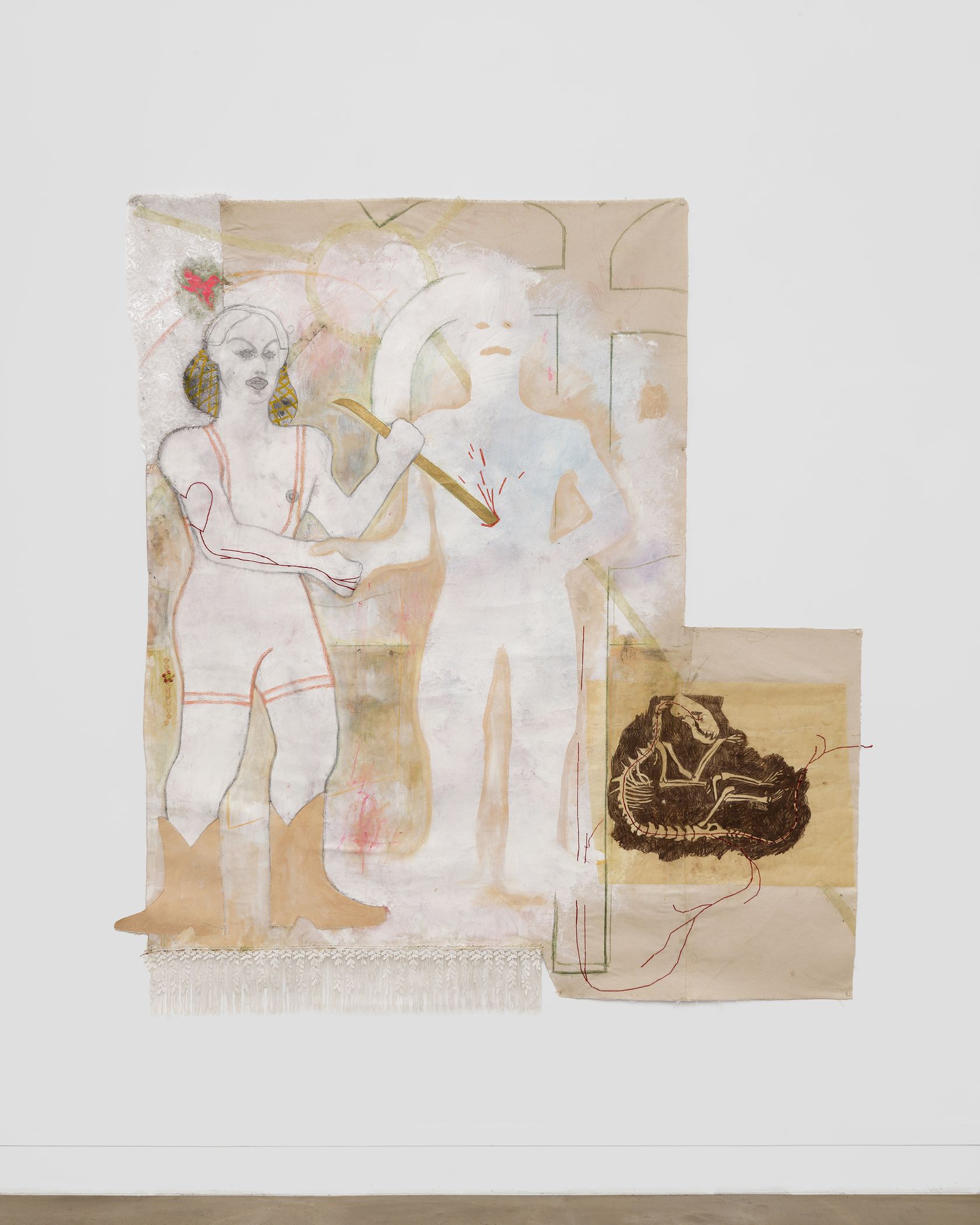

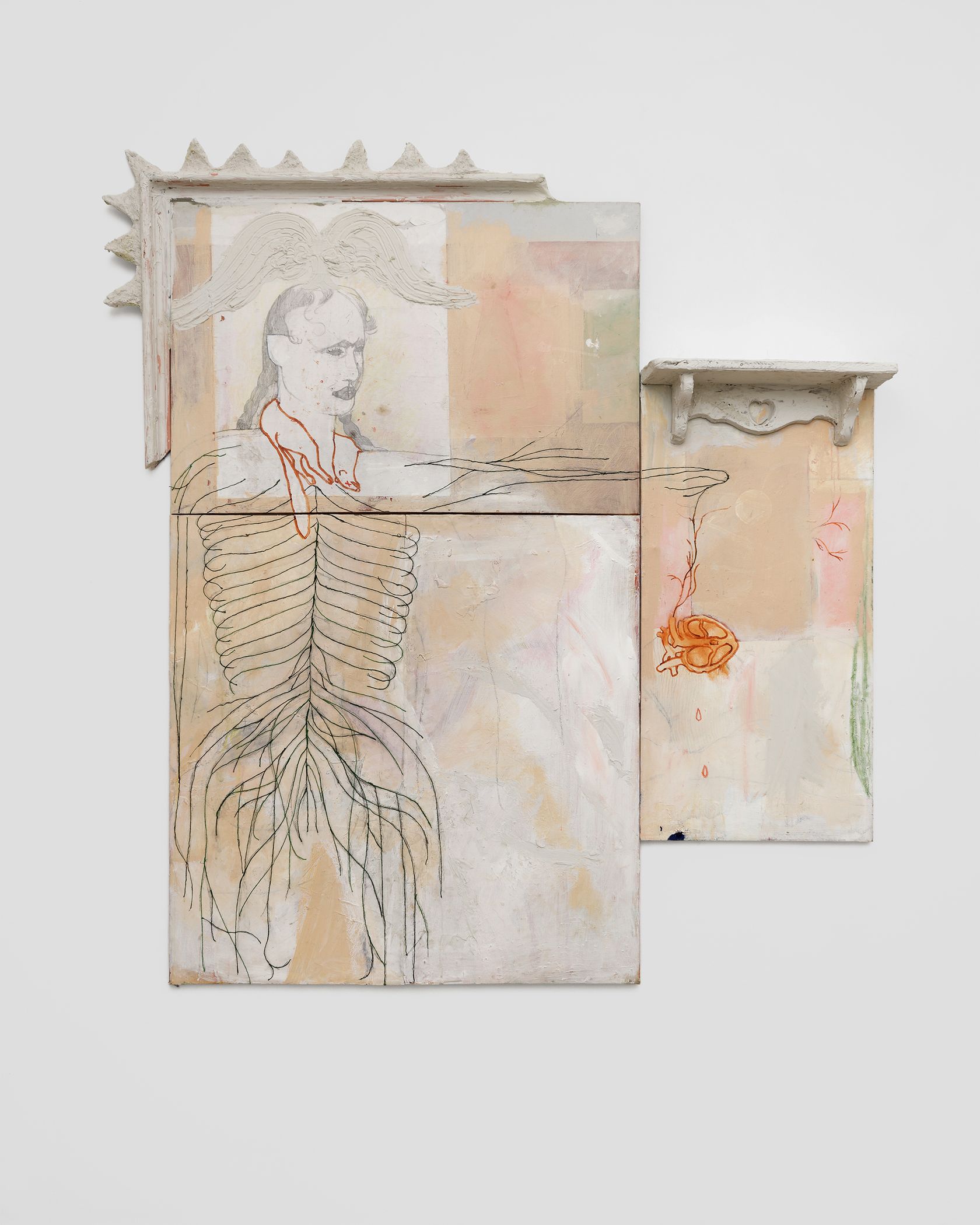

Is it this female colossus with her unstable demeanor, or is it the coat of unbleached titanium white—edgily mixed with salmon pink and hospital yellow— that draws our attention? Are we seeing elements of a pre-Christian fresco or a kind of camp pantheon? The figures—perhaps just like Amy Bravo herself?— brandish spears, stakes and arrows. Bursting with fury, they retaliate against demonic menaces of uncertain motivation. Yet, the more these vengeful giantesses proliferate, alongside other mythological creatures—a psychopomp rooster accompanying departed souls on their route to the heavens, the mongoose skull devouring a snake, a bull and a minotaur...—the more Amy Bravo’s lines disintegrate to reveal a longed-for queer constellation: a community of lesbian warriors in unstable poses, acting out the oral histories of the Afro-Cuban diaspora.

Perched on cloudy banks of fog, these queer archangels seem to find it difficult to remain upright. These milky clouds of vapor might easily emanate from a Cuba as imagined by the artist: “Cuba’s fog not only feels indicative of the island’s climate and light, but the inherent culture of mysticism that is created around its physical unattainability [...]. I live in the fog of displacement that follows many Cuban Americans, and from there I paint.”(1)

These eerie clouds are nourished by a Caribbean culture of mysticism and impregnated by a diasporic imagination based around bric-a-brac: photos, souvenirs, knick-knocks, unspoken words and needlework. Of course, the hazy, unbleached titanium white on which these figures—in the form of ungainly women—are perched, is reminiscent of certain features of Ana Mendieta’s work (1948- 1985), or that of Belkis Ayón (1967-1999), while gently keeping a distance from them.

Amy Bravo equates Ana Mendieta’s Siluetas more with a recurring motif from art history—the mirror—than a primitive symbol of an eco-feminist future. It is not so much a reflection or narcissistic projection of Ana Mendieta but rather a “cleft” divulging a concealed aspect of our planet, a kind of “visual echo” according to Amy Bravo. “These Siluetas also allowed her to see herself where she was not in a geographical sense, as they all pointed directionally toward Cuba, indicating the desire to return to the place she had been torn from.”(2) The same mirror effect led Amy Bravo to move back and forth around the solitary female figure of Princess Sikan.(3) In the same way as Ana Mendieta, Belkis Ayón, and later Amy Bravo, developed a fascination for the beliefs, myths and rituals inherited from Abakuá. According to Amy Bravo, the mirror held out to Belkis Ayón by Princess Sikan allows—and even encourages—transgressive episodes. Like impermanent states of somnambulism, these transgressive sequences transformed Belkis Ayón’s plasticity as well as her movements in space and time. This is of course what magical rites are all about. Far from reinforcing the essentialist links between spiritual culture and Caribbean identity, Belkis Ayón both expanded and nourished this mystical iconography. Amy Bravo, in turn, is fascinated by the relationship to space in her frescos, which are at the same time both dreamlike and radically political. She increasingly sees her paintings as “spaces that open up beyond their surface (sometimes literally through building inset boxes and shelves within the work) and in the sense that they enable me to see myself in a place where I am absent (Cuba, or my amalgamation of it).”(4)

Thus, the surfaces of the canvasses Disinherited (Bullseye), At the Blue Door and An Agreement (all 2023) are no longer enough in their own right: they are either enhanced by a frame-cum-bedhead designed for a wake or augmented and expanded by objects placed here and there on the canvas itself, often with nods to the needlework practiced by the women of the Bravo family—red threads and cords, family placemats or curtain fringes. If Amy Bravo is exploring the tradition of assemblage, it is not with the great, white, male artists such as Rauschenberg, Kaprow and Kienholz in mind, but rather from the point of view of a kind of “Frankenstein”(5) approach to sculpture. In this case, the doctor’s creature would be wrought from gestures and reflexes inherited from the sewing and embroidery as practiced by the artist’s mother and grandmother. And moreover, what does it mean to be a Bravo, the artist wonders with puzzlement? “I found myself musing on the legacy of the Bravo family, questioning what it meant to ‘be a Bravo.’ Did it mean helping to liberate your island from colonialism? Did it mean coming to America and assimilating with conservative patriots? Did it mean shutting up and listening to your father when he tells you he’s voting Republican again, even after you and your brother, who feels particularly terrified as a transgender person, have begged him to reconsider? Did it mean rebelling against your father instead? I sought help from the dictionary. The most common definitions state that to be a Bravo means to be a hero, to have valor, or to congratulate someone on a job well done. In Medieval Latin, it means to be a cutthroat villain, or more specifically, a hired assassin. I was enticed by this dichotomy. I wanted to create a hero who was an assassin and a rebel. I wanted her to wreak ancestral havoc.”(6)

Each scene of vengeance would be reminiscent of the baby teeth preciously conserved by Amy Bravo’s mother, planted in the ground in a ritual invented by the artist. The aim of the prophecy—of her prophecy—would be to regenerate the family’s sense of identity and roots, based on queer, trans and radical, left-wing, existential experiments. According to the artist herself: “Because my teeth are essentially made of sponge, I’m hyper aware of them, feeling the zing of their nerves when I bite down. Perhaps this is why they found their way into my work. Little seeds of bone rotting in my mouth, with roots made of nerve endings. I imagine planting them. What magic would make them grow? [...] Could you regrow a person by planting their teeth?”(7)

The queerness of Amy Bravo’s work, far removed from the academic and institutional traditions of collections, archives or even the duty of remembrance that is transformed into history—practices that are obviously necessary but which have become overly scholarly, I think we all agree—breathes new life into and reaffirms the magical power of healing, the orgasmic rage of redemption, the Abakuá that is deeply rooted in our bodies. With great pugnacity and courage, Amy Bravo’s works poke fun at a global village of supremacists, puffed up with “petro-masculinity”(8) and ready to fight. It’s up to us to perpetuate and extend the spirit of this “dance of the furies.” And we can make a start in our own imaginations...

Géraldine Gourbe

_

1. Amy Bravo, I Still Love You, Despite Everything, MFA Thesis, Hunter, The New York City College, 2022, p. 27.

2. Amy Bravo, op. cit., p. 23.

3. Sikan is a female character, who was sacrificed in Abakuá mythology. Abakuá is a secret, Afro-Cuban men’s initiatory society.

4. Amy Bravo, op. cit., p. 24.

5. Amy Bravo in conversation with Phillip Edward Spradley: https:// fadmagazine.com/2022/05/20/ a-conversation-between-amy-bravo-and-phillip- edward-spradley/

6. Amy Bravo, op. cit., p. 8.

7. Amy Bravo, op. cit., p. 15.

8. Cara New Daggett, “Petro-masculinity: Fossil Fuels and Authoritarian Desire”, Millennium: Journal of International Studies, vol. 47, no 1, September 2018.