-

1/32

1/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

2/32

2/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

3/32

3/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

4/32

4/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

5/32

5/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

6/32

6/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

7/32

7/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

8/32

8/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

9/32

9/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

10/32

10/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

11/32

11/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

12/32

12/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

13/32

13/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

14/32

14/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

15/32

15/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

16/32

16/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

17/32

17/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

18/32

18/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

19/32

19/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

20/32

20/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

21/32

21/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

22/32

22/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

23/32

23/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

24/32

24/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

25/32

25/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

26/32

26/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

27/32

27/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

28/32

28/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

29/32

29/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

30/32

30/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

31/32

31/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

-

32/32

32/32

Steve Gianakos, Who's afraid of Steve Gianakos ?

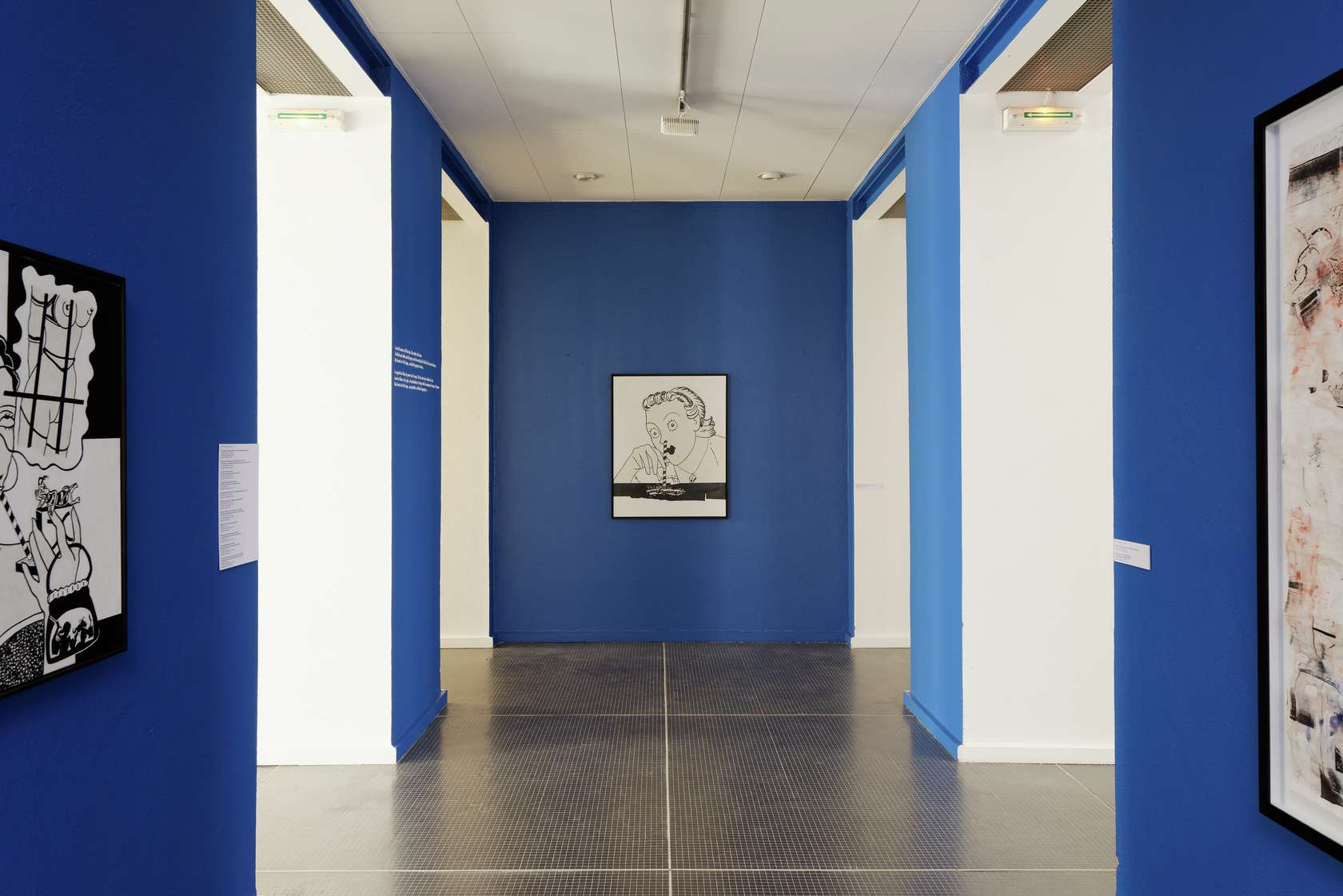

Who’s Afraid of Steve Gianakos? There are plenty of reasons why this little word play borrowed from the title of Edward Albee’s play, adapted for the cinema by Mike Nichols in 1966, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962) might cross one’s mind when contemplating the oeuvre of the New York artist Steve Gianakos.

First of all, because the mid-sixties was around the time when Gianakos began to exhibit his early drawings in the US and it was at the very center of the Pop Art explosion on one hand and the remarkable appearance of Minimal Art on the other, that he developed his artistic language and universe.

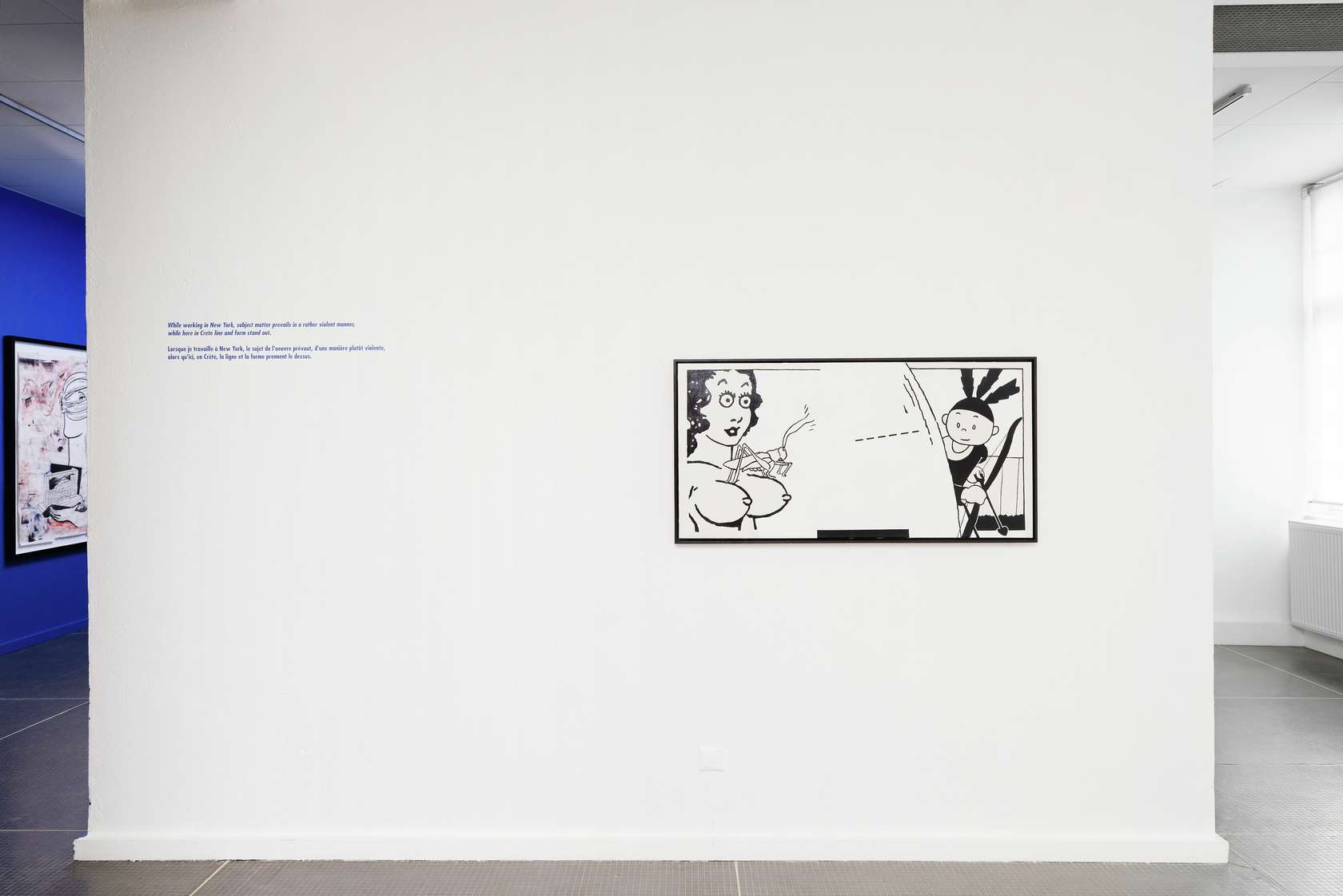

Otherwise there are literally hundreds of reasons to be afraid of Steve Gianakos: His oeuvre cobbles together different elements, poaches from others, touches every aspect of art while respecting nothing, pillages Picasso, Dada and Surrealism as well as comics and illustrations from children’s books from the 1950s. The artist cuts out, photocopies, glues, paints, draws and generally mistreats his objects and figures, which are full of holes, with their throats cut and bodies dismembered to be glued back together, head over heels. Shamelessly, Gianakos exhibits sexualized and lascivious bodies used and abused in an ambiance of sex and drugs without the rock ‘n’ roll but with pin-up girls sniffing coke, women with aggressive bomb-like breasts, men dressed up as little girls, serpents lizards snails and other crawling creatures, slithering into any gap or orifice available…

From the clean lines of his paintings from 1970-80, to the photocopied collages that he produced in great number over the following years, his drawing remains precise and his brush-stroke sober, even as the compositions become more absurd, overlapping with no respect for proportion, like a cascade of exquisite cadavers. With a perfect sense of freedom, Steve Gianakos has since the end of the 1960s invented a universe close to that of Pop Art, nourished by popular culture and comic books, yet far too trashy, erotic and bloody to be simply tidied away under the label of American Pop Art. Comparable with Peter Saul, with whom he shares an affection for a certain “lack of taste”, he prefers a more ambivalent form of vulgarity: He plays with falsely naïve images, sometimes borrowed from children’s publications, sometimes from “adults only” comics, flirting with a kind of perversity, which is often restated obsessively. He also works in series: The charming sequence of Chubby Boy and Chubby Girl show off his taste for the trivial whereas the Dead paintings series plays on death and is continued through the numerous decapitated heads and figures undergoing metamorphosis of his recent works on paper and paintings. Shapes, figures, faces, breasts, mouths and costumes are transplanted from one image, from one oeuvre to another through the use of collage, recycling and ceaseless re-invention, while constructing a universe that is both totally coherent and unique.

He takes aim at the politically correct values of puritan America—those of the puritan West—and finds great pleasure in watching them explode in our faces through his joyfully provocative collages, which sometimes seem more Punk than Pop. Eroticism and cruelty, having more in common with Max Ernst than Antonin Artaud, Gianakos takes perverse pleasure in shooting down all the codes and values of good taste and decent behavior and rolling out a parade worthy of Freaks. His caustic (black) humor extends to the titles of his works, which are often meandering and act as plays on words as well as carrying specific meaning.

So, who’s afraid of Steve Gianakos? One of his paintings dating from 1985 depicts a tailor working on a woman’s corset and is entitled Elisabeth’s Taylor. Thus Elizabeth Taylor, the incarnation of Hollywoodian beauty and glamour was reduced to an idea, a hollow image—a simple play on words. Elisabeth Taylor, was also an image of madness, alcoholism and drug abuse and thus the hidden reality behind the American dream. She was also the actress chosen by Mike Nichols to act out the ruin and downfall of the perfect couple in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, a title which takes us back to the Big Bad Wolf of children’s fairy tales and perhaps also the three little pigs singing Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? in Tex Avery’s Anti-Nazi propaganda film Blitz Wolf (1942).

While one is observing and writing about Gianakos’ unclassifiable and triumphant oeuvre, why not adopt his warped and twisted mindset. All the more reason to exclaim “Who’s afraid of Steve Gianakos? Certainly not us, certainly not us…”

The exhibition at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dole brings together around 80 paintings and works on paper, created between 1980 and the present day. It is something of an ambitious and joyous retrospective, enabling each and every one to discover the breadth of Gianakos’ work, its coherence and at the same time the variety of different pathways in terms of form, artistic technique, iconography and intellect that he has continued to explore to the present day. They are exhibited within an institution, which itself has no fear of the big bad wolf and which for many years has taken great pleasure in providing a platform for atypical, unclassifiable, inappropriate and even toxic artists. Such was the case with Peter Saul, Giakanos’ friend and compatriot as well as French artists such as Rancillac, Fromanger, the Cooperative de Malassis and numerous others, who have fed the rebellious spirit of the contemporary art collection at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dole.

In Dole, Gianakos is in good company, at home almost…

Amélie Lavin