-

1/14

1/14

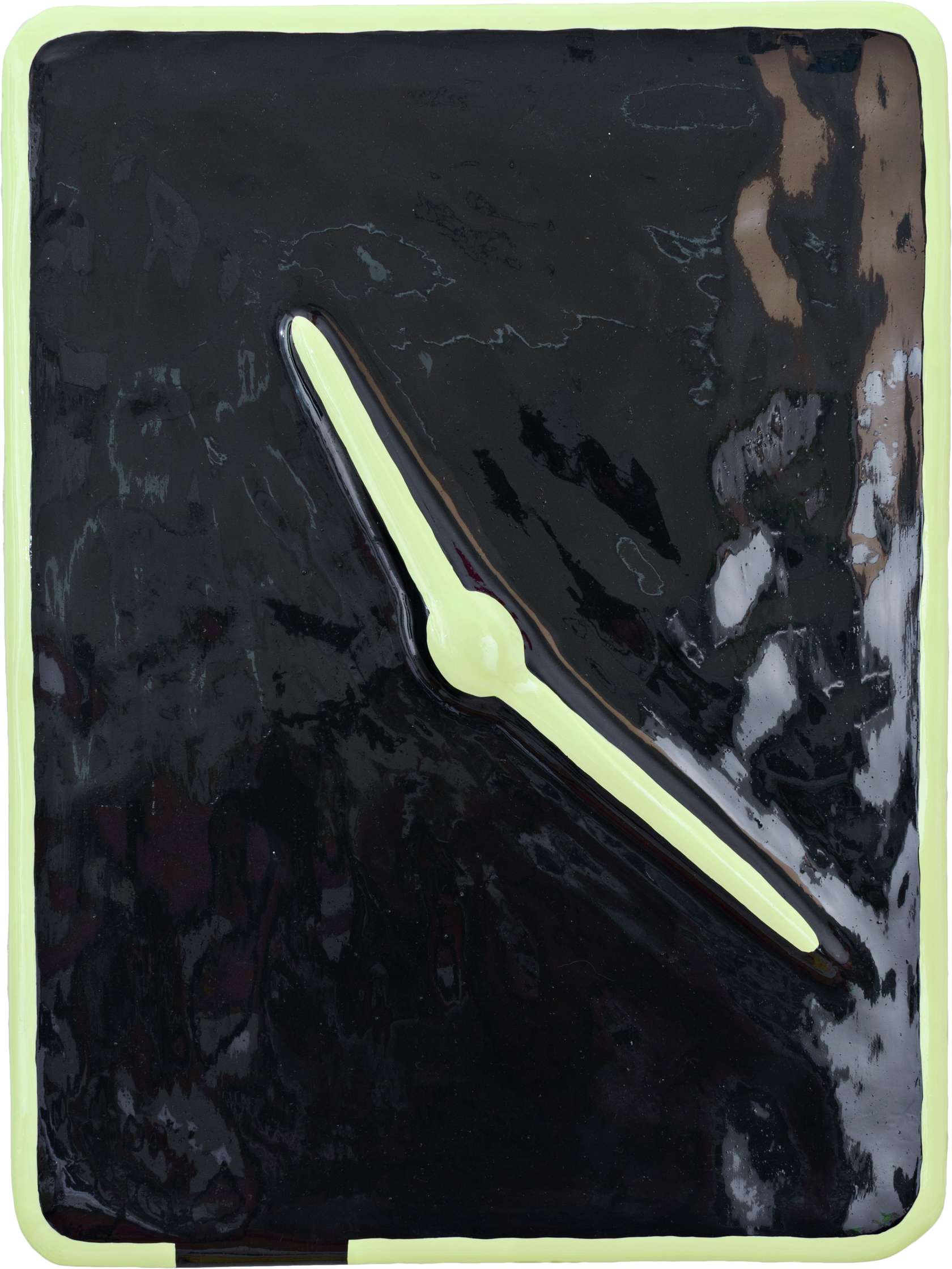

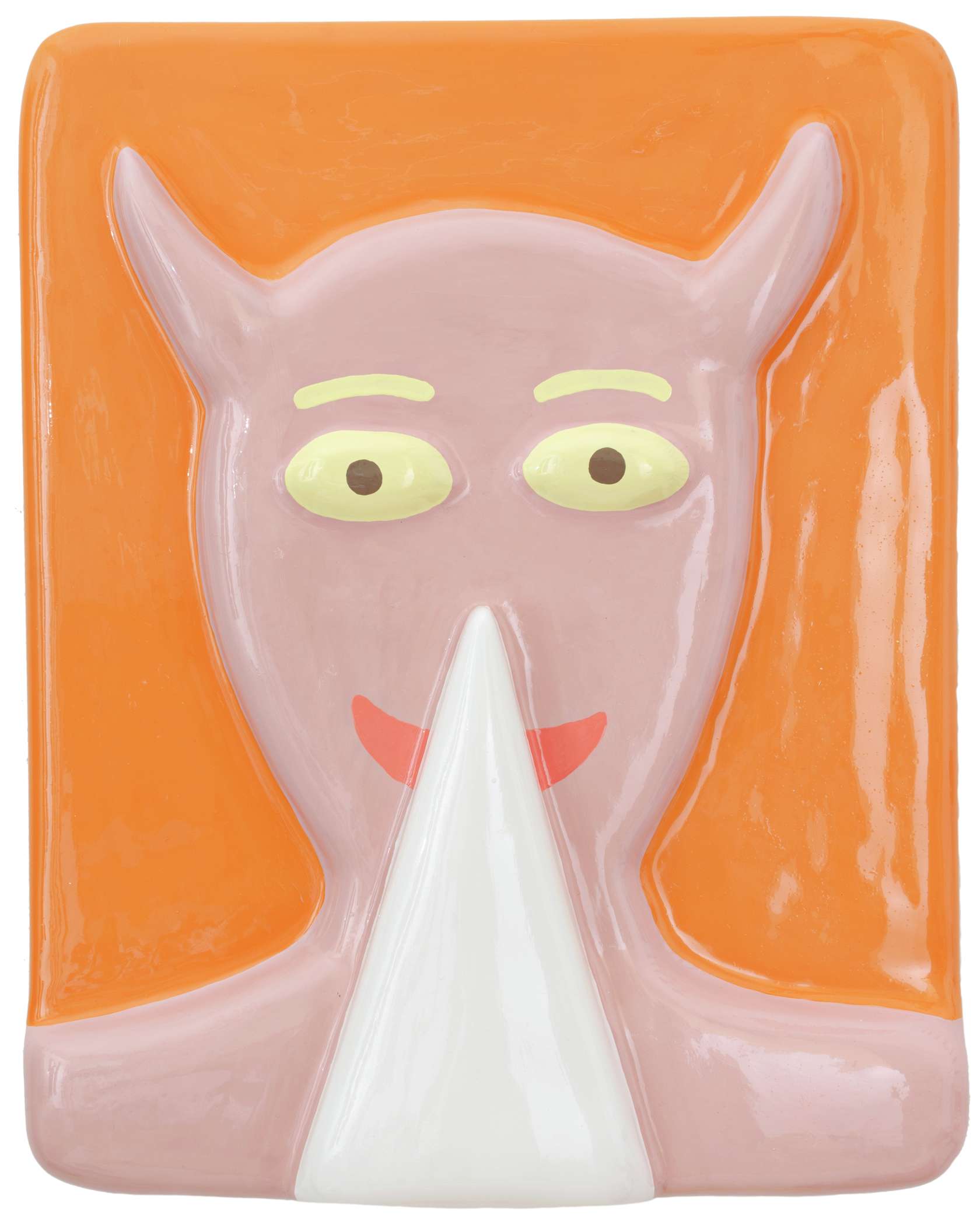

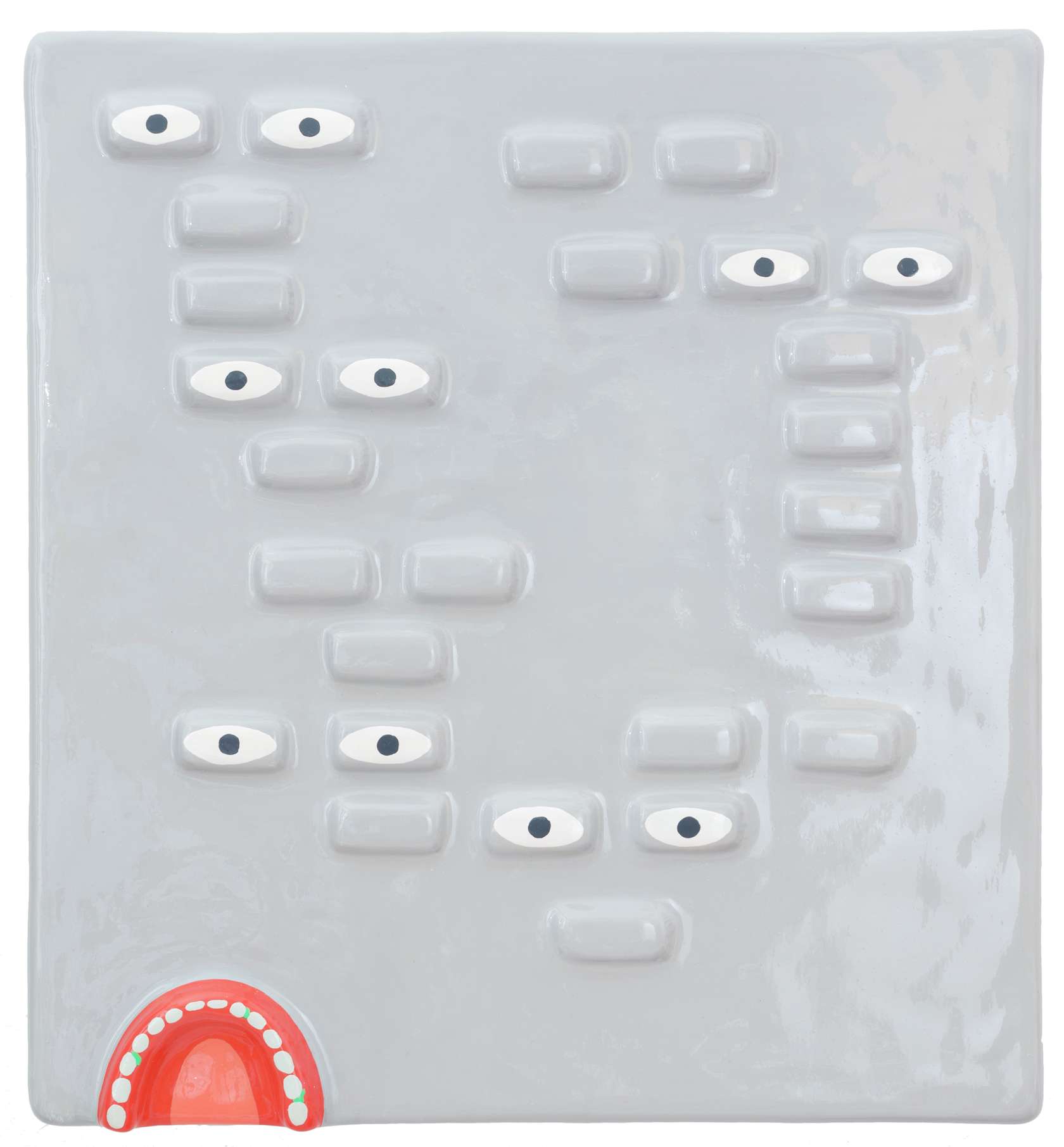

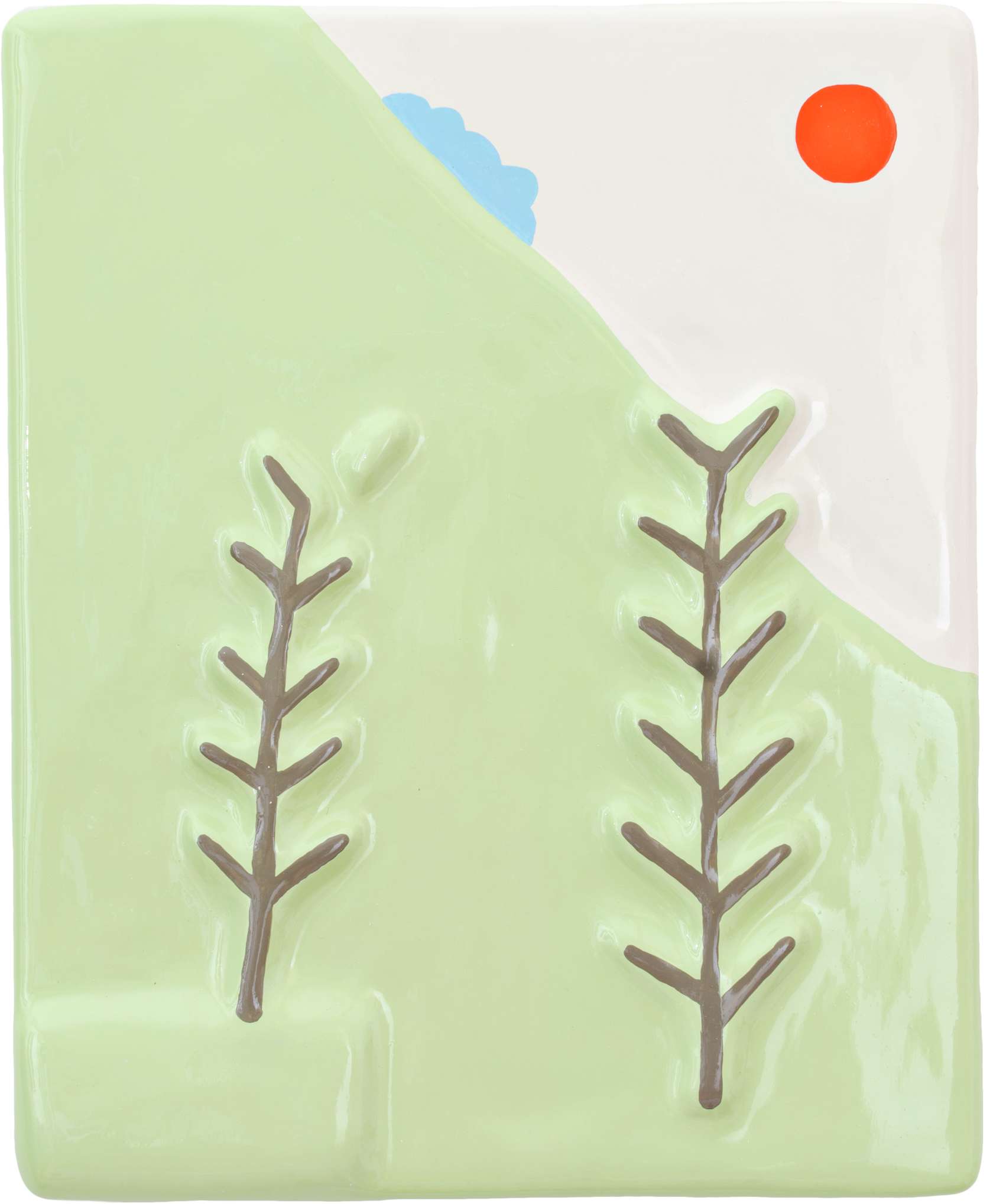

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

-

2/14

2/14

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

-

3/14

3/14

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

-

4/14

4/14

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

-

5/14

5/14

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

-

6/14

6/14

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

-

7/14

7/14

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

-

8/14

8/14

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

-

9/14

9/14

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

-

10/14

10/14

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

-

11/14

11/14

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

-

12/14

12/14

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

-

13/14

13/14

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

-

14/14

14/14

Louis Gary, Magic Saliva

At first sight, the oeuvres of Louis Gary leave an impression of freshness, almost like the tang of a mouthful of fresh fruit at the height of summer. This freshness however, does not come easily. Listening to him, we quickly understand that the artist’s approach to this figurative and colourful élan involves a great deal of care. Indeed the Greenbergian interpretation of modern art, amplified by the insights of conceptual thought, has led to an emphasis on the production of reflexive, cerebral art that addresses reason without passing through the prism of the body. On the contrary, Louis Gary’s works embrace a great sensory and formal liberty, inherent to the non-dualist philosophies that accompany him on a daily basis.

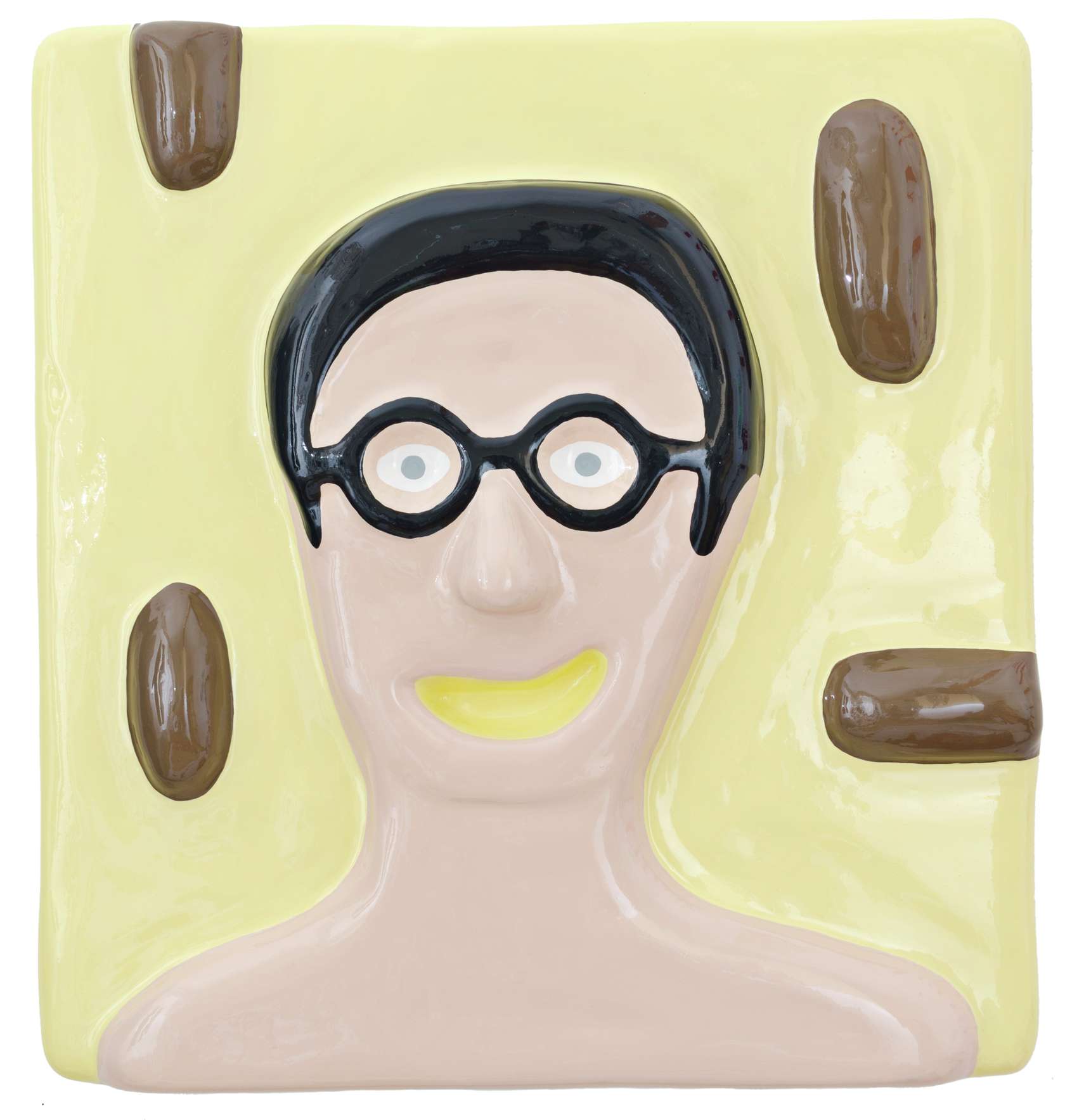

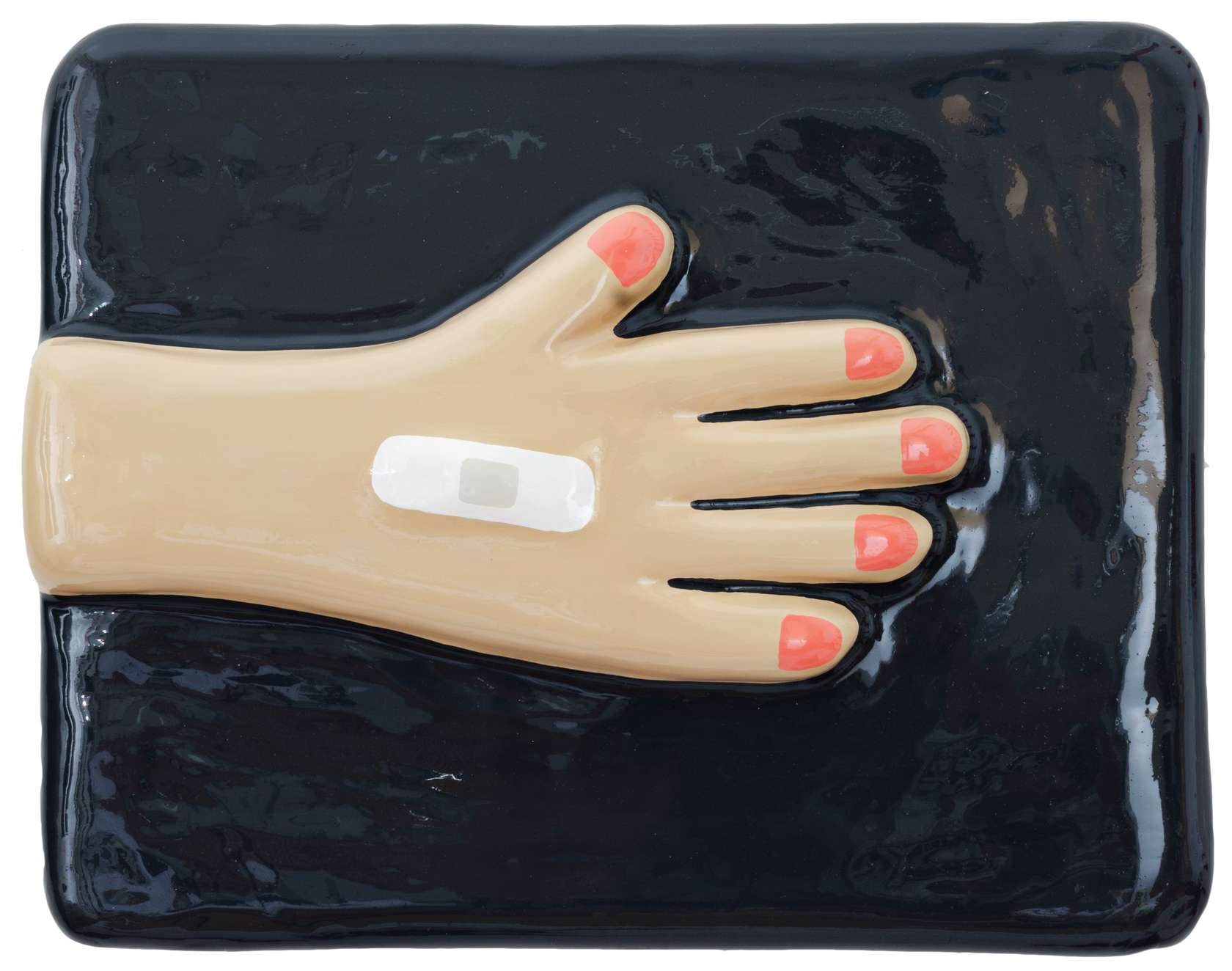

In reference to the series of bas-reliefs on show at Semiose Gallery for the exhibition “Magic Saliva”, Eva Prouteau speaks of “the decorative as a precept of proximity.” Somewhere between a gallery of portraits, naïve landscapes and simplified depictions of everyday objects, these works question the notion of distance—between human beings of course, but also between people and things. Lets try and unravel these ideas together. The decorative relates more to the home than the museum or gallery. It thus represents a more direct relationship than a sacralised work of art ever can. Its functional dimension renders it more effective and enables it to contribute more to the everyday lives of men and women; in ordinary settings, precisely where people enjoy a touch of humour or colour rather than the usual overall greyness.

The way in which these bas-reliefs are constructed allows a better understanding of the issues at stake. They are figurative pieces that combine wood, Styrofoam and painted plaster. The techniques used are those of façade designers, model makers and movie set decorators. The artist covers the structures with ordinary oil-based gloss paint, as a house painter would do. Thus there is real humility in the way Louis Gary produces his work. He might equally have chosen to work with ceramic and be part of the traditional lineage of craftsmanship of the so-called minor arts, whereas instead he embraces the knowhow of ordinary workers even more enthusiastically. Louis Gary’s early works included a lot of furniture as he was exploring the relationship between furniture and sculpture in a manner similar to that William Morris had in mind in Arts & Crafts. Morris made utilitarian and decorative objects at the lowest possible cost in order to enhance the domestic surroundings of every social class. At the same time, as Louis Gary states, there is also an animistic rapport, which is “somewhat primal in nature, like that which causes a child with a high fever to lend his shelves a soul, or perhaps to be passionate about a door knob,” that led him to focus on furniture.

So Louis Gary’s art, very “pop” in style, has little to do with Andy Warhol’s Pop Art, which was a combination of popular art and mass consumerism. Here, even if these bas-reliefs might seem close in form to the sculpture-paintings of a Tom Wesselmann, they embrace a culture that is on a human scale, and in all its simplicity. Some of the colours Louis Gary uses originate in the 1960s and 70s; they are those used in the implementation of postmodernity within our living spaces, but here there is no branding nor any highlighting of desire or pleasure as in Wesselman’s oeuvre. On the contrary, the bodies in Gary’s work, if there at all, are expressed through the stigmata of a wound masked by a Band-Aid, a figure on all fours, or forms that resemble excrement. His bodies are indeed far from the advertising clichés that populate the collective imagination of Western modernity. Moreover, his palette has much more to do with those consciousness-expanding moments we might feel when observing the tiny details of everyday life, such as a doorknob, the wheel of a car or a colour chart for gouache paint. It’s amusing to note that, even if Louis Gary’s works are very far from realism, they are imbued with a truthfulness far more sincere than the charade of advertising, and by extension Pop Art with which they might a priori have been assimilated… wrongly.

The imaginary world of these bas-reliefs is populated with absurd figures or associations that seem to form an escape from situations that are as banal as they are comical. A particular impression emerges: that by allowing us to discover his questioning and dreams, the artist is inviting us to unfold our own relationship with the world. Louis Gary points out that in his creative process, he adds layers that are separated by long drying times. Thus, the artist never goes back in time, in a similar way to history, which is deposited by segmentation, both inside and outside of our beings, without us being able to modify it. We can however analyse it in order to learn from its complexity, like the artist, who in his workshops, asks question that that are only apparently simple: what is a flower? What is a dream? Or even what is a finger?

Charlotte Cosson & Emmanuelle Luciani

Translation: Chris Atkinson

Charlotte Cosson & Emmanuelle Luciani are exhibition curators, art historians and French art critics, specializing in contemporary art. As a Duo, they are co-editors in chief of the CODE South Way magazine and founders of the Southway studio arts community. They exhibited their research on popular, rural and rustic forms in contemporary art in “Pre-Capital” at the Panacea in Montpellier in 2017. In 2019, they have presented “Les Chemins du Sud”, tracing the history of art from the South of France, at the MRAC in Sérignan. In 2018, at the invitation of Neïl Beloufa, they were nominated for the Ricard Foundation Prize.