-

1/9

1/9

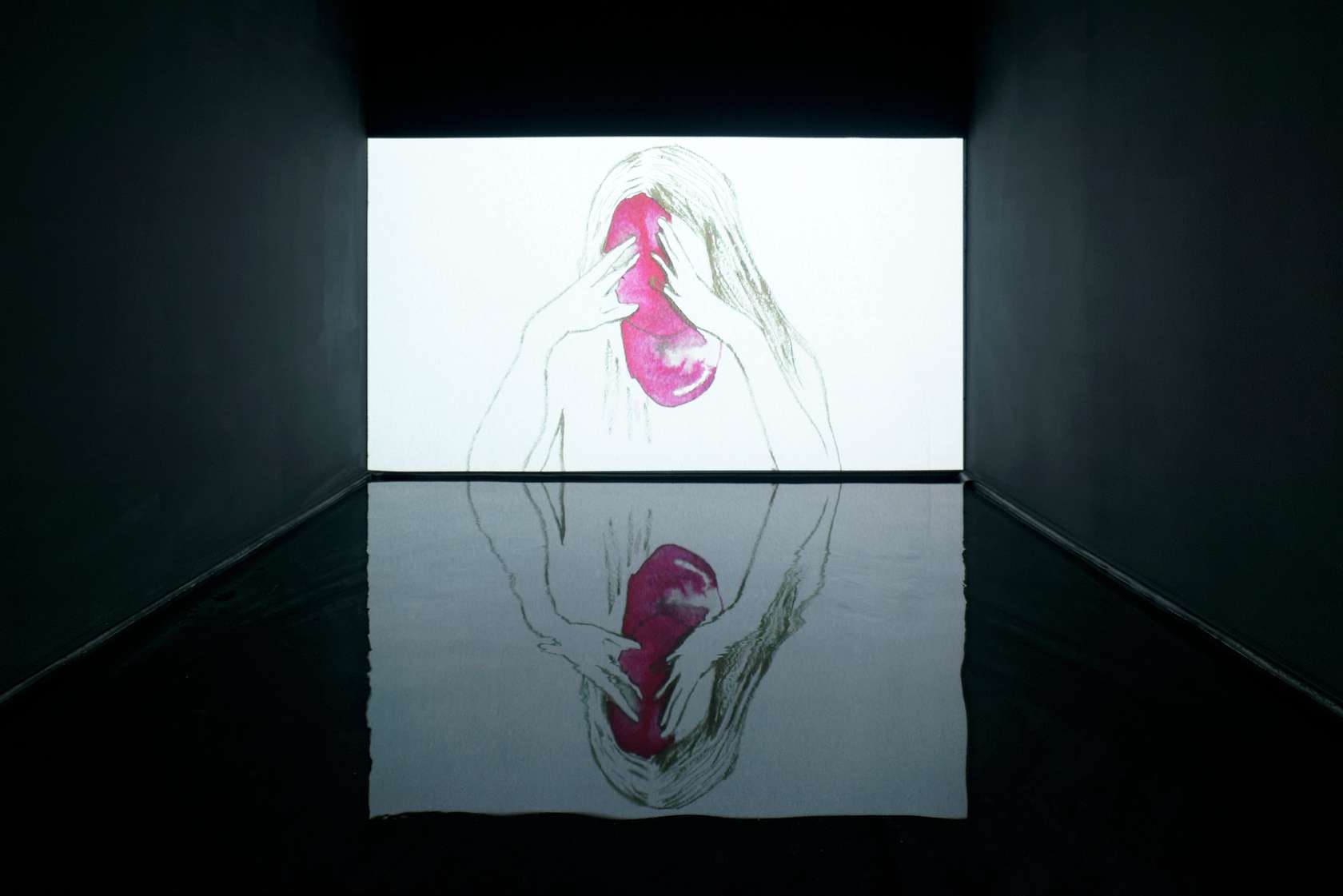

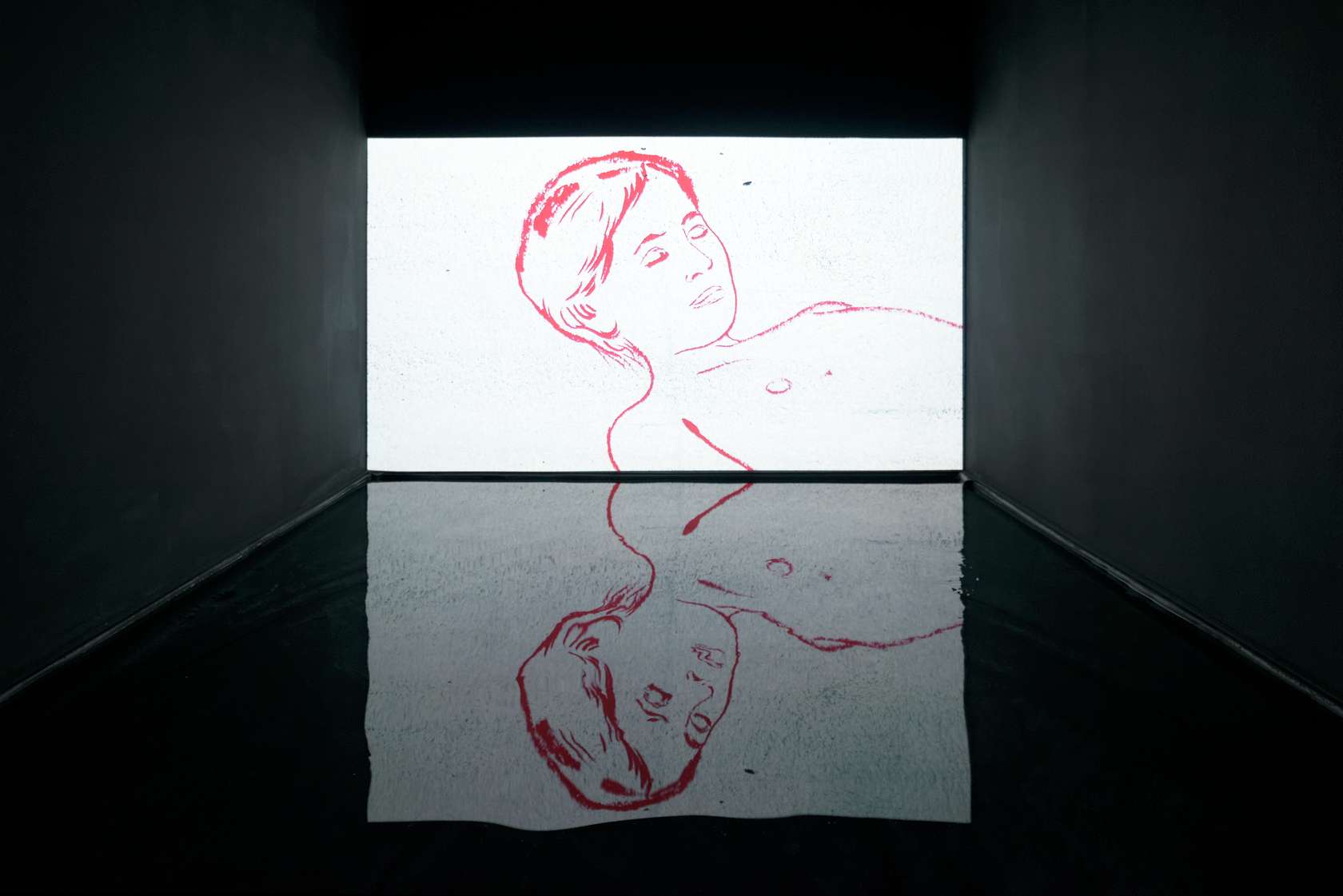

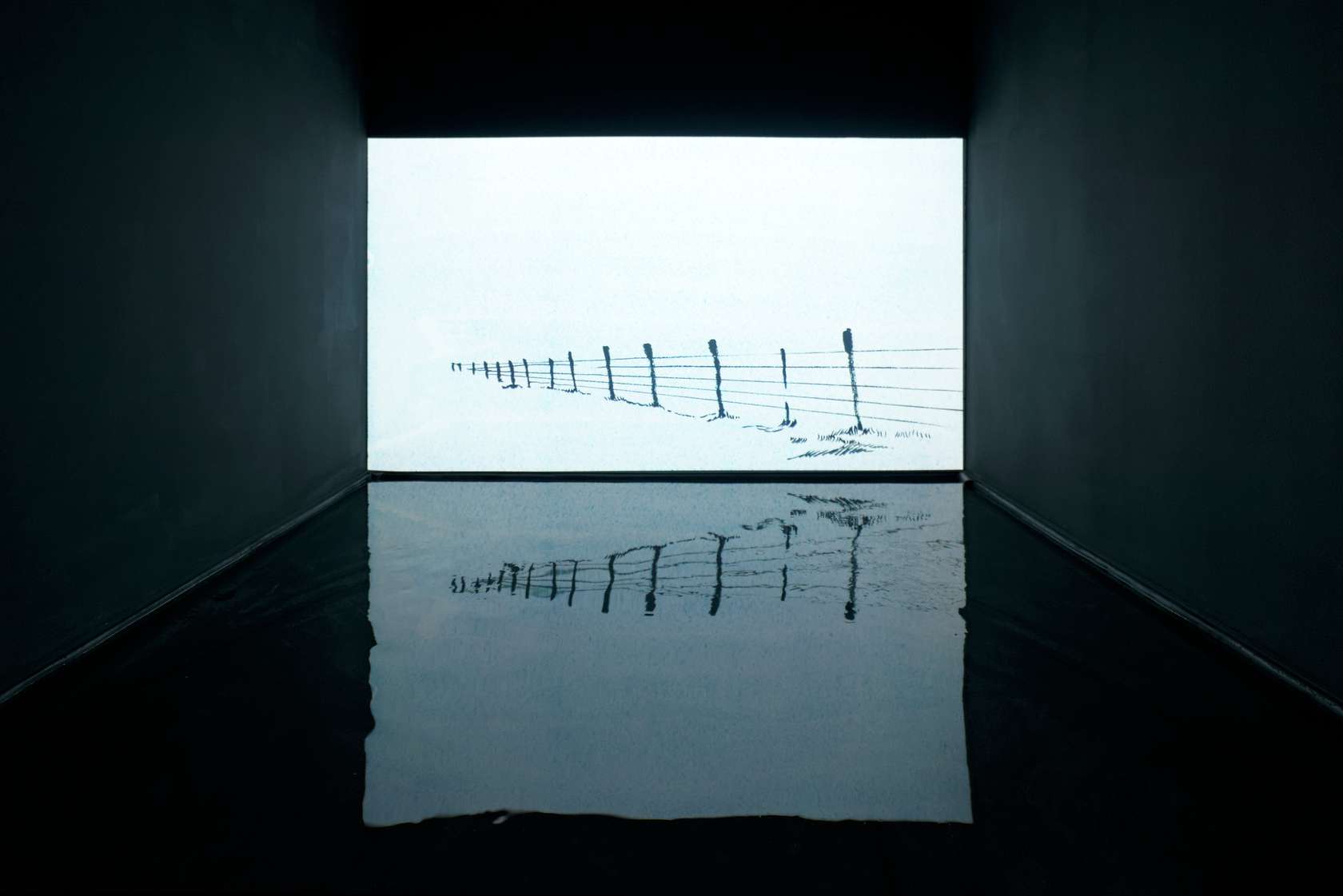

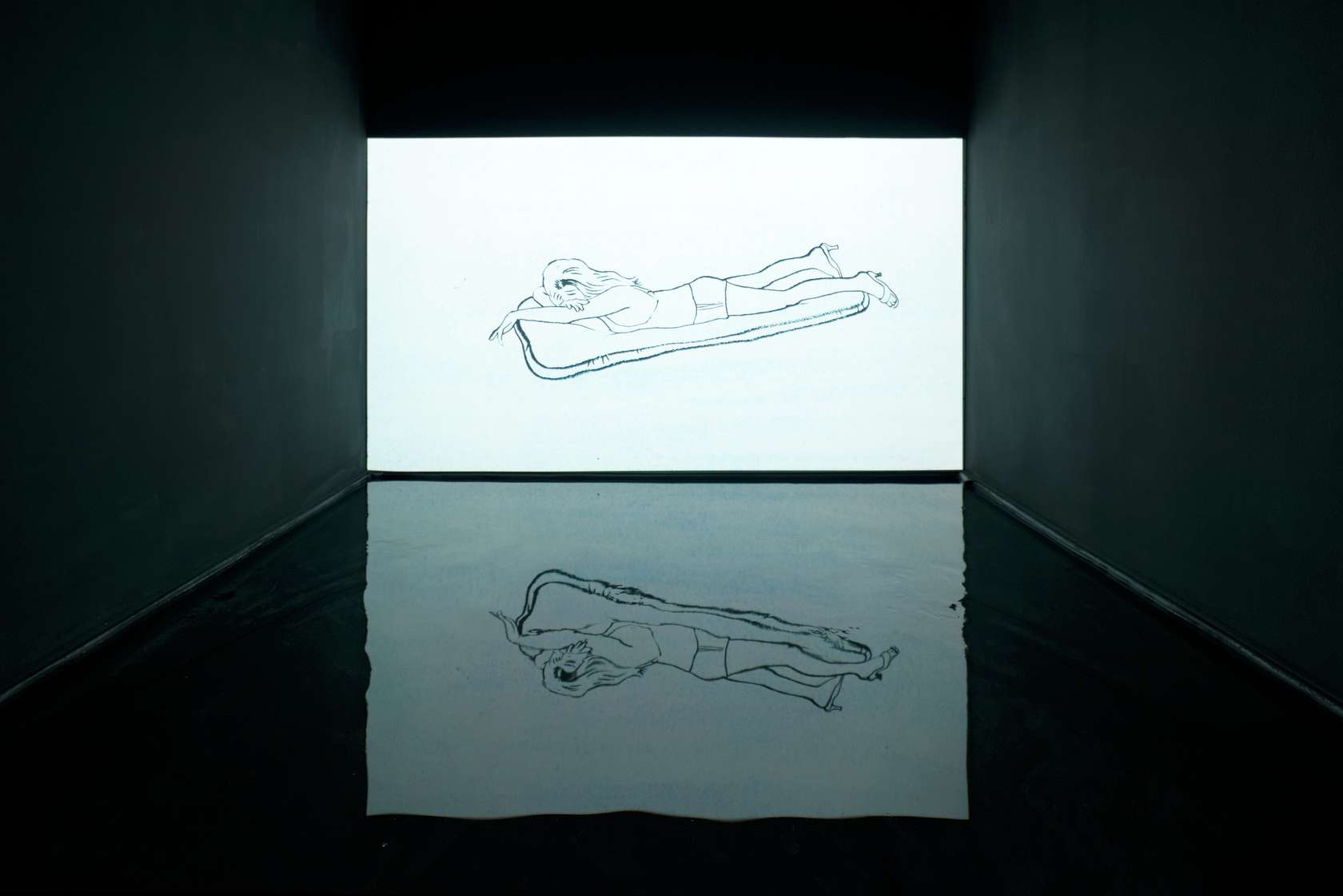

Françoise Pétrovitch, Échos

-

2/9

2/9

Françoise Pétrovitch, Échos

-

3/9

3/9

Françoise Pétrovitch, Échos

-

4/9

4/9

Françoise Pétrovitch, Échos

-

5/9

5/9

Françoise Pétrovitch, Échos

-

6/9

6/9

Françoise Pétrovitch, Échos

-

7/9

7/9

Françoise Pétrovitch, Échos

-

8/9

8/9

Françoise Pétrovitch, Échos

-

9/9

9/9

Françoise Pétrovitch, Échos

To kick off the autumn season, Semiose Gallery throws the spotlight on the oeuvre of Françoise Pétrovitch through a second solo exhibition and the accompanying publication of a catalogue, bringing together in exemplary manner her recent body of work. Two instances, or rather two platforms dear to the artist (exhibition and publication), which above all enable the spectator to envisage other approaches to reading Françoise Pétrovitch's oeuvre, to get away from the more obvious routes to understanding via narrative and poetry.

While since the mid 90s, Françoise Pétrovitch has clearly adopted as her own a vocabulary associated with adolescence and childhood, and by extension its symbolism and mythology, this has been less through a desire to expound on the "subject" and rather one to explore the "genre".

The figures of young girls and boys that recurrently appear across her works on paper, her paintings, mural drawings, sculptures and installations are above all archetypes and are completely disassociated from any narrative. They are figures in action, playing blind man's buff ("Colin-maillard",2014), holding hands ("Sans titre", 2011,) braiding each other's hair ("Sans titre", 2014) or involved in other everyday activities. Occasionally they even go as far as to torture or mutilate each other. These archetypical figures, simply defined as either male or female, reoccurring from one oeuvre to another, are ultimately perfectly interchangeable.

Playing on the formal variations framing these archetypes further motivates Françoise Pétrovitch's work. The video entitled Echos (2013), from which the exhibition draws its title, is emblematic of this and even pushes the idea a little further by setting up a dialectical relationship between its variations. Echos is made up of a montage of a series of drawings alternately showing figurative images of the above-mentioned archetypes, detached details of bodies and completely abstract images composed of landscapes of colours similar to Rorschach tests or Apollinaire's "Soleil cou coupé". The consecutive images fade into each other, the apparition of a new image as the previous image recedes producing an ephemeral effect of one image superimposed on another on both the screen and the spectator's retina. The artists refusal of any temptation to create a hierarchy within the images, to attempt to classify them or create a narrative, leaves the spectator face to face with a series of impressions; the eye becomes a receiver of information, information, which is of course subjective but at the same time pure and devoid of any a priori meaning. The only sense of any importance here is that of vision, through which the succession of colours and shapes intensify or are multiplied to infinity and whose exteriorization the pool of water placed beneath the screen incarnates, its surface resonating like a retina.

It is in this way that the images, whether they are in two or three dimensions - drawings, paintings or sculptures are perfectly "evocative": they try their utmost to lead us away from the well-trodden paths of narration.

This exhibition uncovers the pathway taken by a body of work, an artistic practice driven by a constant play on composition. In this context, it is worthwhile noting more precisely the importance of the question of "genre" or artistic category: the portrait, the still-life and even the "verdure" (from the art of tapestry: a wall hanging composed of a décor showing vegetation or animals), in order to understand that Françoise Pétrovitch's work is also an echo of the whole history of art itself.

Leslie Compan