-

1/6

1/6

Ernest T., La Smoud Emotion

-

2/6

2/6

Ernest T., La Smoud Emotion

-

3/6

3/6

Ernest T., La Smoud Emotion

-

4/6

4/6

Ernest T., La Smoud Emotion

-

5/6

5/6

Ernest T., La Smoud Emotion

-

6/6

6/6

Ernest T., La Smoud Emotion

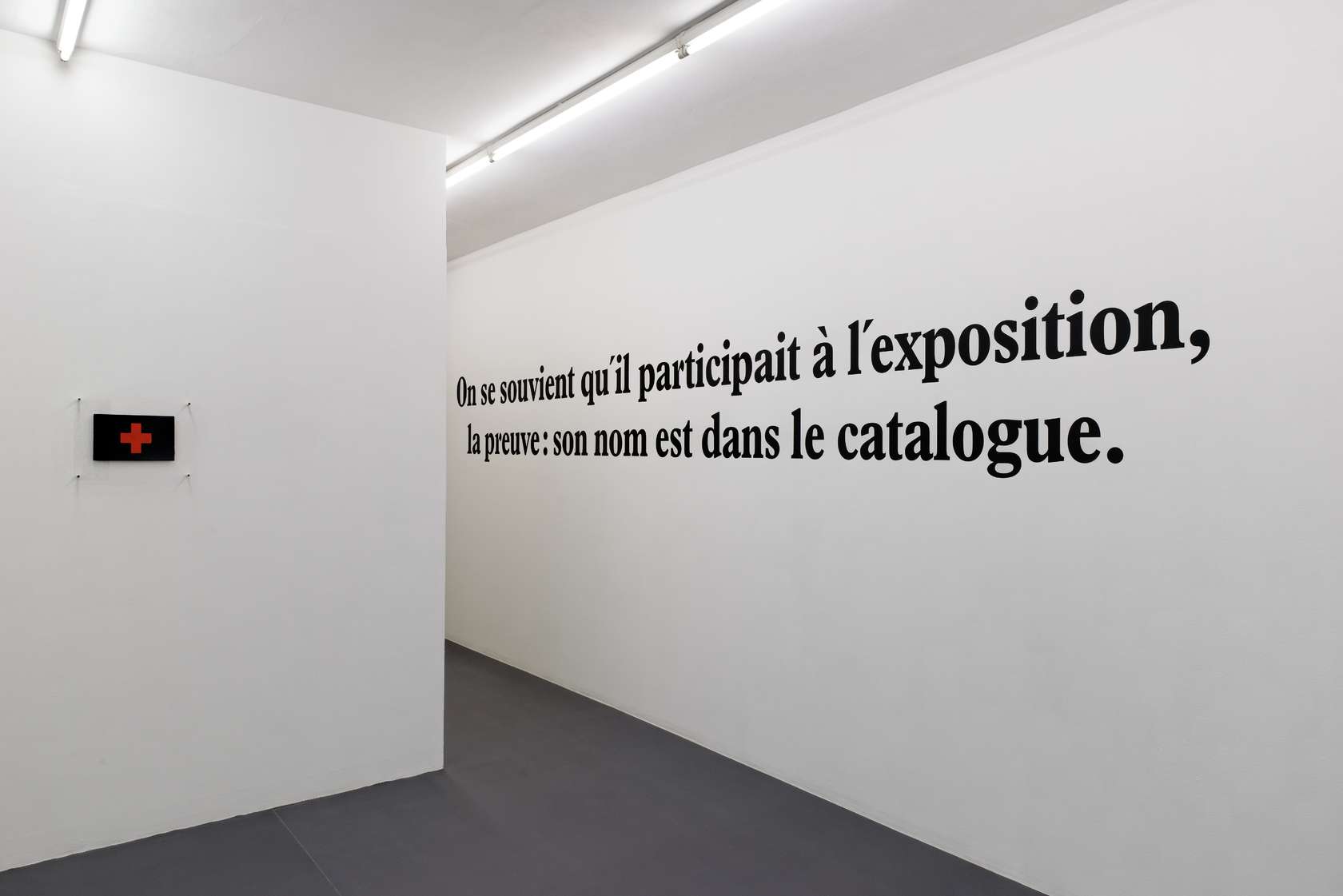

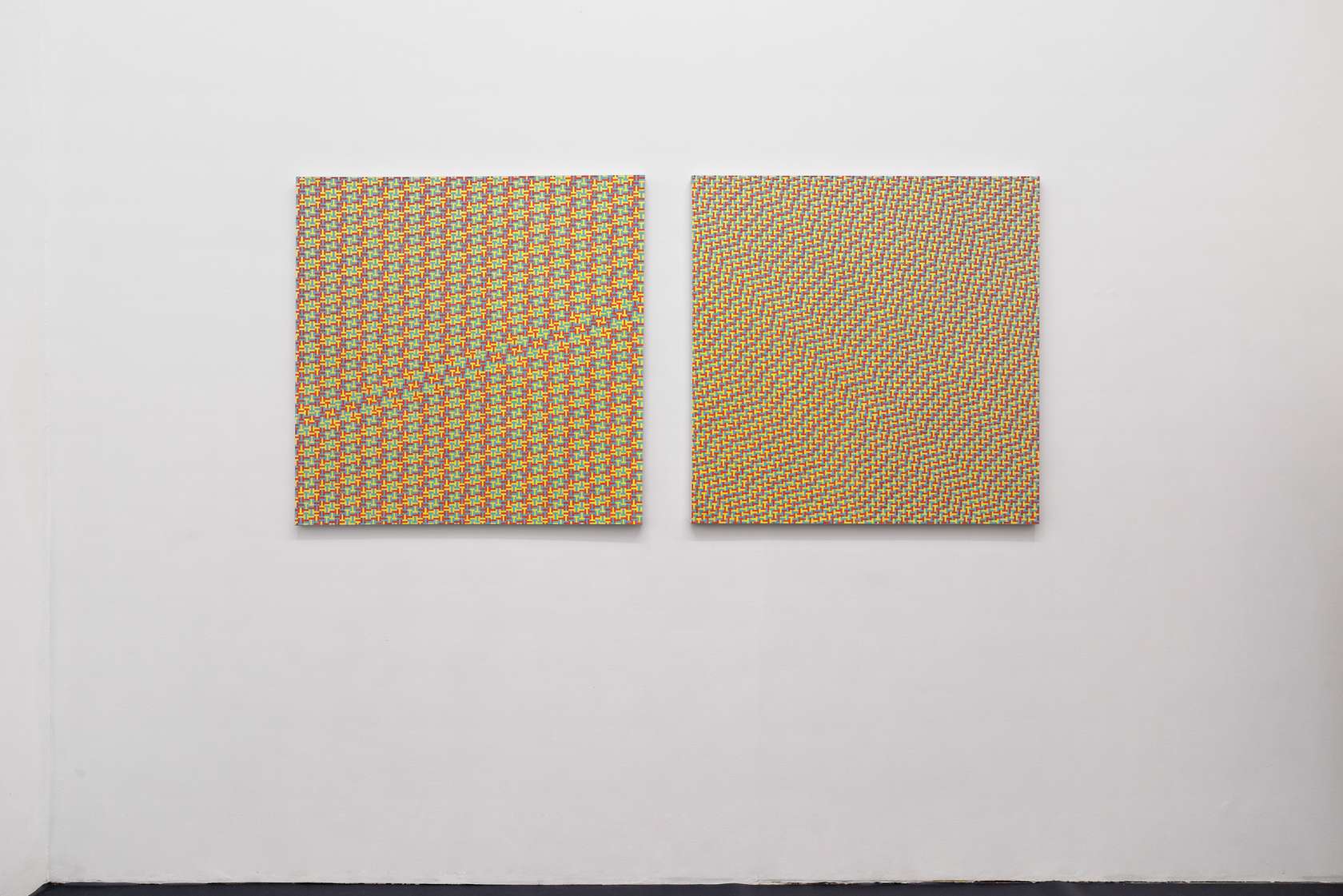

A fleeting glance through the showroom window of the Semiose Gallery should be enough to convince any passer-by of the presence of an historic exhibition. If for some reason or other the series of abstract geometric paintings composed of the same module of a black square on a white background wasn’t enough, then the conceptual statement plastered on the facing wall should do the trick. And even if he or she hadn’t identified the master’s stylistic abdication from the street, they would surely recognise his stance from the writing, especially when it means banging ones head in order to finish reading it – in any case, has there ever been a better way of getting avant-garde ideas across to the spectator? This proposition, where the imperfect dares to imitate lyricism, in fact exploits this remarkable pretention to sobriety, while it’s rather charming avoidance of the subject simply furthers the cause of every artist, even the most mediocre: the quest for glory. Employing the approach of setting out a hypothesis then testing it out in practice, Ernest T. wrote the same thing in different terms, as a full page in the press: “the true artist is also a strategist capable at any given moment of occupying the field (the page (or wall)) effectively but without ostentation. It would be inappropriate to criticise him for this as his productivity simply serves to maintain his position within the world of art, whilst awaiting recognition.” (Public N°1, 1984). True to his word, the artist set about producing pictures. The title of the first series: Les Peintures Nulles (Useless Paintings), would lay down the programme for a whole body of work. They consisted of a combination of square modules formed of the artist’s self-proclaimed pseudonym and using three (almost) primary colours. This is the kind of brainwave that certain artists have constructed an entire international career around; the masterstroke that ensures optimum visibility, while allowing the artist to shine with heroic modesty for having refused any stylistic signature; a ready made recipe for an enduring and perhaps even endemic oeuvre, with success assured in proportion to the phenomenon created, or even the promise of working comfort normally associated with handicrafts, i.e. always repeating the same actions while never producing the same result. In short by achieving perfect uselessness, Ernest T’s paintings have been presented to the world as objects of pure speculation, unspoiled by any of the values that the different legitimising bodies might wish to confer and thus creating their own raison d’être. It is patently obvious that Ernest T. confronts the world of art on equal terms, by acting with impeccable bad faith, disconcerting naivety and above all a taste for fakery, while taking aim at the certainties conveyed by every era and in particular their criteria for establishing taste and critical pertinence.

It is well known that the wisdom of radical art is expressed through its concession to the authentic pleasure of painting and to the relative moderation of pure form, occasionally leading to more baroque digression. In a similar manner, the maturity of Ernest T’s oeuvre shows through here as the product of an occupation as equally healthy and stimulating as a Sudoku puzzle. His mathematical suites reaffirm the label of mechanistic painting done by hand, while titillating the irrational at the heart of the algebraic logic and decorative (as well as therapeutic) virtues of a system, which to the great displeasure of its creators, has never found a serious application. As for the Smoud paintings – an in sounding term that betrays its own outmodedness - they persevere in obstinate respect of the same protocols and balance of colours, their aesthetic value guaranteed by an effect of déjà vu.

Julie Portier