-

1/9

1/9

Amélie Bertrand, Queens & Kings

-

2/9

2/9

Amélie Bertrand, Queens & Kings

-

3/9

3/9

Amélie Bertrand, Queens & Kings

-

4/9

4/9

Amélie Bertrand, Queens & Kings

-

5/9

5/9

Amélie Bertrand, Queens & Kings

-

6/9

6/9

Amélie Bertrand, Queens & Kings

-

7/9

7/9

Amélie Bertrand, Queens & Kings

-

8/9

8/9

Amélie Bertrand, Queens & Kings

-

9/9

9/9

Amélie Bertrand, Queens & Kings

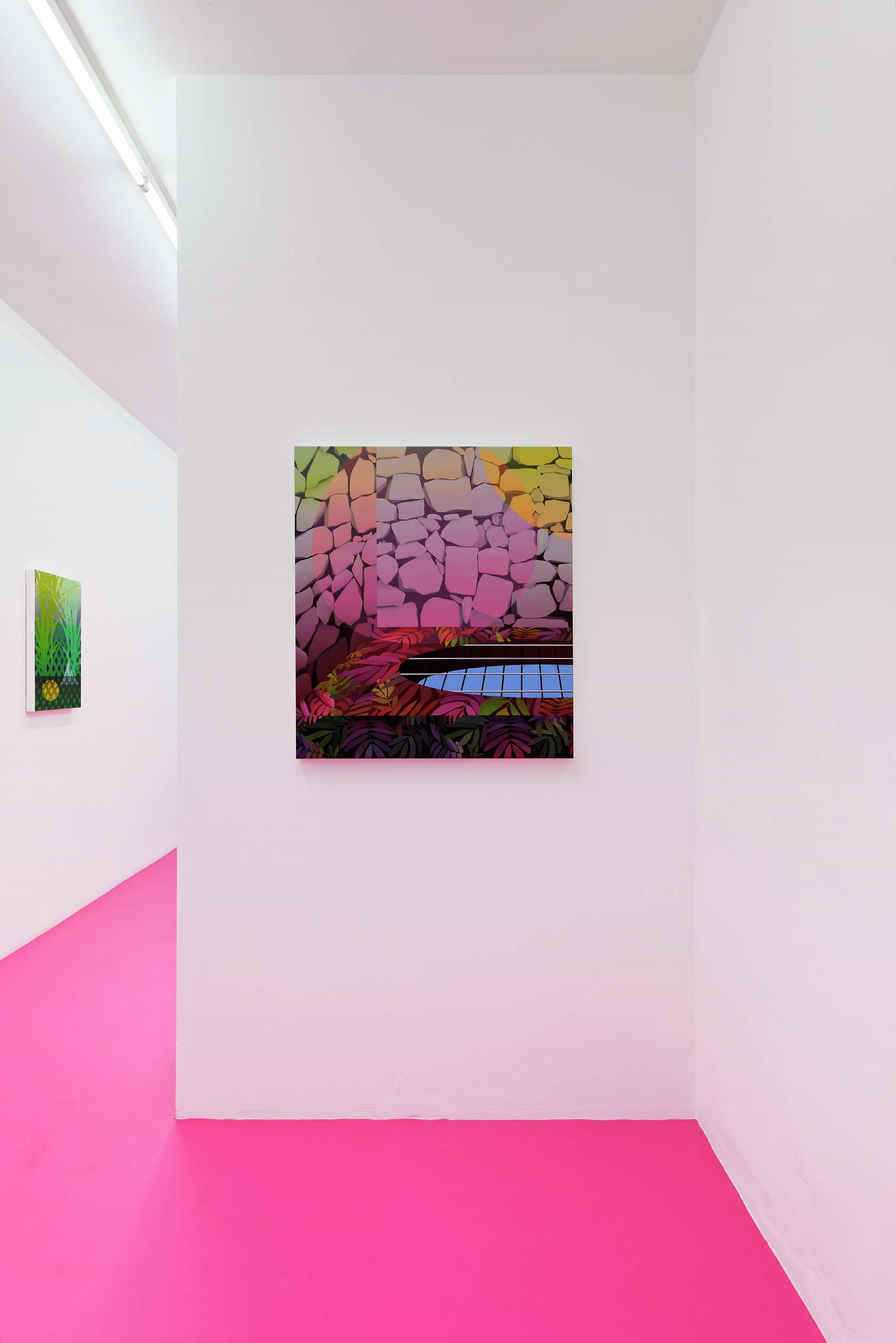

L'Avventura on pink lino

Amélie Bertrand has the first name of a girl while her second is more of a boy's. It might not seem much but it's a fine starting point for a painter whose brushes constantly point in opposite directions: When Duchamp used to disparage the odour of turpentine, it's a safe bet to say he was referring to the illusory giddiness that its vapours caused amongst its blissful devotees. For a love of painting is worth nothing if it does not simultaneously secrete its antidote, hatred, the deeply felt loathing inspired by its profoundly decorative bourgeois complicity, its defining artifice. The entire quality of a medium hangs on its plasticity, its ability to express contradictions simultaneously. Since the paradox of "Schrödinger's cat" at least, we have been aware that a being (and a fortiori an artistic practice) can be both dead and living at the same time: the question is no longer so much one of knowing how the superimposition of states might be possible in the quantum world, but rather why should it not be possible in the real world seen on our own scale?

This is the reason all today's great painters are quantum; my only reaction is one of approval when Amelie Bertrand confides that she admires John Currin or Sigmar Polke's work, and I'd add Philippe Mayaux myself. Félix Fénéon, the critic, who prided himself on his ability to measure the value of a metaphor by Mallarmé using a dynamograph and to reduce the paintings of Degas to mathematical equations was the first to understand, and he passed his secret on to Seurat.

As whole regiments of present-day painting have superimposed an infantile faith in the image over a nauseating love for painting, the photographic model has established itself as an unsurpassable horizon, with Gerhard Richter as its prophet. Yet Francis Picabia had already cut this idea to pieces in 1921: The "Merry Widow" in question in his Veuve Joyeuse is in fact painting itself. Logically, it was through the use of a computer that Amélie Bertrand (like Philippe Mayaux) solved the riddle of "Schrödinger's cat" with a mouse: "Photoshop has enabled me to open up a whole field of possibilities and at the same time completely distort them. That's why I never use 3D software. Everything would be just too accurate", she says.

Her most recent paintings explore this idea of distortion in all its forms simultaneously with great panache and with such mastery that the organization of her coloured surfaces in a similar way to the Dashboard of a Mac ©®, produces a quite stunning result: certain sections of the paintings are blurred though veils of semi-opacity, or slide from left to right or in the opposite direction, mini-applications modify the different layers through various functions; from a simple drag and drop, she invents unprecedented colour gradients, lights coming from behind the paintings - closer to the sexy pallor of LEDs than picture-postcard sunsets, ripples, impossible 3D turnarounds, a world that is both hermetic yet without limit, dense yet deserted, suffocating, oppressive and at the same time infinitely and eternally restful.

Against a background of cheeky fluorescent pink lino, Amélie Bertrand has laid out her paintings, which resemble characters from Antonioni's Avventura, trapped in a psychological and moral adventure, which makes them act against established conventions and criteria of a bygone world. At last.

Stéphane Corréard